Several hundred years ago, someone had the foresight to take a couple of pointed sticks and use them to manipulate a length of yarn into a series of interconnected loops in succession to create a fabric. Somewhere along the way, this activity came to be known as knitting, which has become a popular hobby for people of all ages today though in the past it was more associated with grandmas. Ironically, the same simple process used to make favorite homemade hats, sweaters and scarves has evolved into one of the most flexible and versatile fabric-forming technologies known to man. Consumers love knit fabrics and consequently, their breadth and diversity of applications only continues to grow. It’s virtually impossible to proceed through one’s day without directly using, wearing, encountering, or benefiting somehow from knit fabrics in some form or another.

Germany-based Karl Mayer Textilmaschinenfabrik will launch two new double-bar raschel machines for warp-knit spacer fabrics this spring. These types of 3-D fabrics are finding applications in shoes and other technical applications.

Knits are most commonly known for their natural softness, bulk, stretch, recovery and conformability. However, knit fabrics also offer excellent engineering opportunities because of the knitting process’s inherent ability to manipulate, control and secure individual yarn placement. This unique capability enables a designer to enhance the fabric’s look and feel, affect color placement, alter depth and surface texture, and generate a whole host of other fabric characteristics. An engineer can impart physical properties, create openings of various sizes and shapes, and control porosity and fiber placement. Several knitting techniques also allow for the creation of individual “whole garments,” seamless tubes and complex-shaped products.

Knit Structures: Weft

Virtually every knit structure falls into one of two primary categories commonly referred to as either a weft knit or a warp knit. As a general rule, weft knits are formed by a yarn or multiple yarns fed as one to all selected needles, including grandma’s, which is then manipulated into a series of interconnecting loops. On weft-knitting machines, the yarn is directed to the needles across the machine’s flow direction. For this reason, weft-knit stripes generally run across the width of the fabric. Because knit fabrics are composed of a series of interconnected loops, which are not necessarily locked in place, weft knits can be deknit, unravel or “run.” Weft knits lend themselves better to fashion and apparel related applications, and are more compatible with spun yarns and natural fibers, though filament yarns also can be used. Given the continuing blurring of lines between sports and yoga wear, and casual, business and everyday apparel, its not surprising to learn that roughly 90 to 95 percent of all weft-knitting machines in production today are used for apparel-related applications.

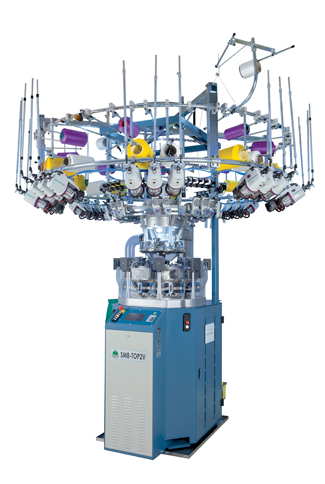

Italy-based Santoni S.p.A. specializes in seamless knitting machinery such as the Santoni SM8 Top2 single- jersey, electronic circular knitting machine.

Knit Structures: Warp

Warp-knit fabrics almost always are machine made and can be manufactured at much wider widths than weft knits. Contrary to weft knits, warp knits are formed as numerous individual strands of yarn — the warp — are guided to select needles in the machine’s flow direction. Warp knit stripes typically run the length of the fabric. Subsequent machine cycles reposition the guided yarn over a different needle to create the warp knit fabric. This interaction of the guided yarn to select needles creates a stable construction that, unlike weft knits, is difficult to unravel. Warp knitting, generally better suited to filament yarns, tends to be more oriented towards applications where engineering, physical properties and high production speeds are most beneficial. This includes some areas of fashion, but the structures also are well suited to industrial, specialty and technical fabric applications.

Weft and warp knits each have a variety of distinct types or sub-categories. As technology advances and evolves however, some of these distinctions are becoming more blurry.

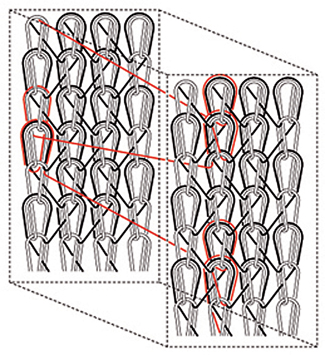

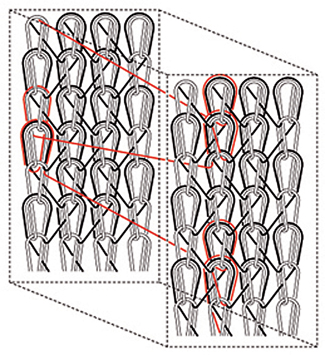

A diagram showing a 3-D variable section of a warp-knit tubular fabric

Weft-Knit Types

Hand knits: As the name implies, hand knitting involves using knitting needles, crochet hooks, human-powered hand knitting machines, or some combination thereof to create knit fabrics. Hobbyists are the mainstay in this category making hats, scarfs, sweaters and other items for personal use. However, there are consumer oriented high-end, handmade applications as well. Because the process is performed by hand, the types of fibers, yarns and constructions used for hand knits are left entirely up to the knitter’s imagination.

Flatbed knits: Flat knitting can be done on a single needle bed — single row of knitting needles — machine or a “V” bed machine where two or more needle beds are set at opposing angles allowing the selected needles to create a “V” for the yarn to be fed into. Heavier, coarser and bulkier yarns, spun or filament, natural or man-made, work well on this type of machine producing fabrics with soft, supple, bulky and relatively open constructions. Applications mostly are geared towards the fashion and apparel industries, though fabrics for gloves, socks, medical and technical end-uses easily can be created.

The advent of 3-D knitting or shaping technology and multi-gauge weft knitting technology allows designers and manufacturers to create even more unique designs, fully-fashioned garments, 3-D shaped fabrics, and for some applications, seamless garments.

Circular knits: Like with flat knitting, a single needle bed or “V” bed configuration can be used to make circular knit fabrics, the difference being that circular knits, as the name implies, are constructed in tubular form. Circular knits typically use finer yarns, and exhibit soft, supple, conformable and elastic characteristics. Again, applications mostly are fashion- and apparel-related. These include T-shirts, dresses, hosiery, socks, underwear and leggings.

Warp-Knit Types

Tricot knits: Tricot-knit fabrics are formed perpendicular to the movement of the needles, which allows for high machine speeds and fabric throughput. Tricot knits are often characterized by their light weight; elasticity; and thin, smooth, silky feel. They are commonly found in a variety of apparel, swimsuits, intimate wear, print cloth, automotive and industrial applications.

Raschel knits: In raschel knitting, the fabric is formed in line with the movement of the needles. There are two categories of raschel knitting machine commonly available: single needle bar — where the needle bar is a row of needles — or double needle bar. The double needle bar machine, as the name implies, has two opposing rows of needles that can be set with a specific gap between them to produce different styles and thicknesses of fabric. This allows the knit loops or stitches to be effectively held in place during machine movements, which provides the ability to make a broad range of very intricate and complex fabric designs.

Single needle bar raschel knits are used in a wide array of applications ranging from lace and lingerie to various netting, medical, industrial and technical configurations. Double needle bar machines are able to make very complex knit structures that can include two different face fabrics interconnected by cross stitches. Applications include seamless garments, smart fabrics and wearable electronics, tubular and compression fabrics, and pile and plush fabrics for a variety of applications.

Weft-inserted warp knits: Weft inserted warp knits effectively use the stitching characteristics of warp-knitting machines to “stitch” together several layers of yarn. The yarn stitched together is flat and has zero crimp to it, which results in minimal unwanted stretch in the fabric. Also, if the ability to insert the non-crimp layers at different angles is incorporated, stitched fabrics with near isotropic strength can be produced. This attribute is highly desired in numerous composite applications. Weft-inserted warp knits also are used extensively as coating and laminating substrates.

Knitting design software, such as Shima Seiki’s SDS-ONE APEX3 design system and its complete 3-D virtual sample imaging component, offer designers the ability create complex knit designs.

Advanced Applications

Obviously, weft and warp knitting can, and does, get much more complicated depending on the application and its end-use requirements. Knitting technology continues to evolve and improve. Developments are led by closer and stronger collaborations between the machine and component manufacturers along with contributions from the end product’s supply chain. Improvements in graphic design software systems give designers and engineers even more flexibility in patterns and strategic yarn placement. These advances allow knit fabric manufacturers to target more technical, non-fashion-related and traditionally woven applications for technical textiles and composites products.

The rapidly evolving technological advances in knitting design, engineering and equipment afford knits virtually unsurpassed versatility with boundless design and engineering opportunities. There are lots of opportunities looking for the right knit.

Knit: A very generic term that covers a wide, wide range of products for an even wider array of applications. A world without knits would be a very dull and less comfortable world indeed.

Editor’s Note: Jim Kaufmann is senior engineer at T.E.A.M. Inc., Woonsocket, R.I.; and owner of NovaComp Inc., Willow Grove, Pa. The article is based on Kaufmann’s presentation given at the 2014 Textile World Innovation Forum.

March/April 2015

.jpg)