D

uPont’s Seaford, Del., facility has witnessed the creation of an enormous world-class

fiber industry including pilot plant assistance in commercializing Dacron™ polyester, the fiber

which eventually would displace nylon as the workhorse of man-made fibers.

DuPont appears determined to maintain Seaford as a world-class competitor and a valuable

participant in the nylon value chain. According to sources, Seaford gradually will evolve from a

fully integrated nylon plant producing a range of deniers for textiles and carpets into a major raw

material supply source for DuPont global nylon facilities.

The company will install modern winding technology in newer facilities and confine Seaford

investment to that needed to increase quantity and improve the quality of flake for DuPont use

around the world. This begs the question: is this the future of man-made fiber production in the

United States?

Nylon In The 90s

Typical of a product well into the

maturity phase of the product life cycle curve, filament nylon has settled into market areas where

it has comparative technical or marketing advantages over competing materials and will not be

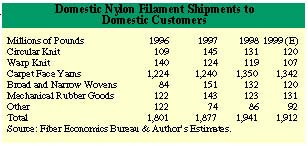

displaced easily by offers of sheer price. As detailed in Table 1, filament nylon shipments today

are a major force in five major market areas defined by fabric constructions.

Obviously, carpet face fibers provide the lion’s share of market opportunities for nylon

filament yarns, with estimated 1999 shipments rising to more than 70 percent of all nylon filament

fibers shipped domestically. All other end uses approximate 110 to 120 million annual pounds each

with some important shifts occurring in the past several years.

Circular Knit

Filament nylon in circular knit

constructions is composed of textured and flat filament yarns in hosiery plus some small amounts of

knit body wear fabrics. After a dramatic rise to more than 140 million pounds by 1995, we predict

hosiery usage of nylon to slip by more than 17 percent to 120 million pounds as the consumer

conducts an anti-pantyhose war.

Nylon hosiery consumption is reduced as control garments containing spandex replace

control-top pantyhose constructions and knee-high stockings appear under increasingly popular

slacks and jeans.

Coincidently, imports of nylon in hosiery deniers also have decreased, suggesting that the

market is oversupplied and prices are weak.

Warp Knit

Nylon use in warp knits has dropped

in the recent past from a high of 140 million pounds in 1996 to 107 million pounds in 1999.

Polyester is the major force behind the shifts. Lingerie and loungewear have converted from

traditional nylon constructions to polyester to take advantage of the recent spate of unacceptably

low polyester filament prices.

Shipments by U.S. producers of fine-denier polyester to warp knitters have fallen 34 percent

to an equivalence with nylon at 107 million pounds in 1999 after outsourcing nylon by as much as 15

percent in 1996.

At the same time, imports of fine-denier polyester (both FOY and POY) have almost doubled

since 1996 with the largest jump, 48 percent, coming between 1996 and 1997 when the Asian economies

headed for the tank. Growth since then has been a more modest 11 percent per year compounded.

It is likely that the nylon and polyester shipments reported above by the Textile Economics

Bureau are understated by diversion of some POY to draw warping constructions for warp knits. It

does not detract from the conclusion that imported polyester filament is having a major impact on

U.S. producer shipments.

Tires And Industrial

U.S. producer nylon shipments to the

mechanical rubber goods (tires plus hoses and belts) industry have settled into a rather monotonous

132-million pound (+/- 8-percent) pattern. Even polyester shipments have succumbed to the ennui,

278 (+/- 3 percent) million annual pounds.

Shipments of high-tenacity nylon have grown by 127 percent since 1996 while shipments of

high-tenacity polyester have grown almost 90 percent.

The absolute value of these increases is more than 81 million pounds, almost 20 percent of

all high-tenacity materials consumed in the U.S.

Wovens

Nylon is used in a myriad of broad

and narrow woven end uses including lingerie, linings, outerwear, transportation fabrics, luggage

and coated and protective materials.

Nylon use in wovens has suffered from the same polyester pressure as its sister fabrications

of mechanical rubber goods, tires and circular and warp knits. Nylon woven fabrics today enjoy a

market share substantially less than 50 percent of what it was in the ’80s. But, where nylon’s

advantages are allowed to shine it performs well.

The depth and breadth of nylon product lines for woven applications plus the willingness of

producers to develop variants for specific end-use applications have helped maintain nylon’s

position in selected market areas despite polyester’s popularity.

Carpet Face

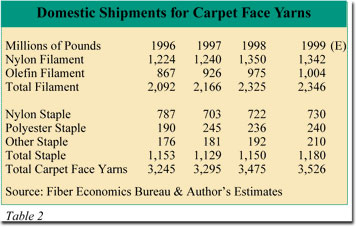

As seen in Table 2, fiber shipments

for carpet face use grew 1.6 percent from 1996 to 1997, another 5.5 percent in 1998 and is

projected to increase another 1.5 percent in 1999. At the same time, total filament shipments to

all end uses grew 4.5 percent in 1997, less than 1 percent in 1998 and are projected to see no

growth in 1999.

Total staple shipments grew 4.5 percent from 1996 to 1997, dropped 2.6 percent in 1998 and,

as with filament, no growth is projected in 1999. Thus, the nylon filament industry, supplying

fibers for carpet face yarns is riding one of the few growth curves in the U.S. man-made fiber

industry.

In 1999 textured filament nylon is the fiber of choice for more than 38 percent of carpet

face fibers, slightly improved from the level achieved in 1994. Filament polypropylene runs second

with a 28.5-percent share, up from 26.7-percent in 1994.

Staple fibers in total still maintain an important position in carpet manufacturing with

total nylon, polyester and olefin products representing approximately one-third of total face fiber

shipments, slightly behind filament nylon and ahead of filament polypropylene.

It is likely that staple’s share will continue to erode as improved filament technology

continues to pressure staple constructions already saddled with the added costs of yarn

preparation.

It is interesting to note that filament nylon’s 1-1/3 billion pounds in carpet face

materials should rise to 23.9 percent of all filament fiber shipments in 1999, up from 23 percent

in 1994.In addition to its technical importance in carpet manufacturing, nylon filament

distribution to carpets is becoming increasingly important to fiber manufacturers.

Because carpet face fibers provide the majority of the nylon producer’s market, new

developments and competitive prices are mandatory to continue this position.

Sustaining Growth

Filament nylon brings value to

several markets, particularly value carpet. These markets are important to nylon producers and add

substantial value to the U.S. economy.

Despite the onslaught of imported manufactured products, it seems that after more than fifty

years, nylon has found its proper homes and is well positioned for continued growth.

Editor’s Note: John E. Luke is owner of Five Twenty Six Associates Inc., Bryn Mawr, Pa., a

consulting firm specializing in strategic marketing and operations facing textile fiber and fabric

manufacturers. He is also a professor of textile marketing at Philadelphia University.

January 2000