Cotton is a responsible, natural solution to the microplastics issue.

By Hank Reichle

The planet earth is home to a growing population that today stands at approximately 8 billion people, each of whom is estimated to own more than 100 articles of clothing, bed linens, and bath-room linens. Of course, while how many articles of clothing someone owns varies widely depending upon multiple factors including affluence, necessity, and individual preference, clothing still ranks right up there on the essentials list with food, water and shelter.

The global textile and apparel industry — supplying tens of billions of products annually to keep people adequately, comfortably, safely or fashionably clothed — is not only supplying one of life’s essentials but is a major economic engine and employer, contributing nearly 2 percent to global gross domestic product and a much higher percentage in many developing countries. It is an important industry, but with such scale, we must mind our impact on earth and its inhabitants.

As the textile industry has evolved, the understanding of its environmental and social footprint has increased as has the acceptance of responsibility for limiting any negative impact and increasing any positive impact. Over the past 15 to 20 years, much of the textile industry’s focus has been on environmentally sustainable and socially ethical initiatives. Most of these initiatives are about how products are made.

Increasingly, however, the newest initiatives are more intently focused on the products’ environmental impacts during and after use. Of course, a product’s impact during these two phases of its life cycle is greatly influenced by its components. As part of this new and justified focus, the global textile industry, especially brands and retailers, will be looking for better fiber solutions to mitigate challenges like microfiber pollution and end of life disposal.

Better Alternative

Cotton, and specifically cotton grown in the United States, offers brands and retailers and their customers a compelling fiber solution because the product is a responsibly produced, natural, renewable, biodegradable fiber with supply chain transparency that includes traceability and key environmental metrics.

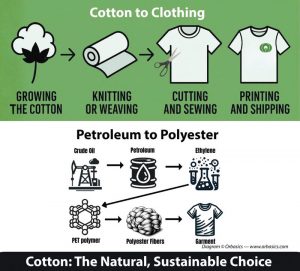

While cotton, and especially U.S-grown cotton, plausibly has a lesser environmental footprint than synthetic fibers in the production phase, fiber production is not the emphasis of this article. Rather, the focus is on how U.S. cotton is positioned to help the textile and apparel value chain address the huge global microplastics disaster that is unfolding and growing land fill challenge. The microplastics crisis is not a textile-specific issue — 12 percent of all the plastic leakage into the environment from unmanaged or unmanageable waste comes from the polyester value chain, and the textile waste that is managed is estimated to occupy 7 percent of landfill space.

The Cost Of Plastic

Undoubtedly, plastic has made life easier, and it is difficult to imagine a world that is completely void of plastic, but there are environmental and human health costs to that convenience. Plastic poses significant problems because it is not biodegradable. Rather, it breaks down into micro-plastics and nanoplastics that taint the earth’s sea, freshwater supply, soil and air.

Consumers are increasingly aware of the issue with plastics, and they are slowly but surely starting to make the connection that polyester is plastic and that their clothing choices can have a huge impact on the environment and human health, including their own. Because clothing, sheets and towels shed the fibers of which they are made when worn and laundered, they are constantly releasing microfibers into the air and water. Cotton products shed more microfibers than polyester; but when those cellulosic cotton fibers enter the environment, they break down through the process of biodegradation just as nature intended. Conversely, the microfibers of polyester and other synthetics are not targeted by the microbes responsible for biodegradation because they don’t recognize them as natural food sources. Those microfibers contribute to the microplastics crisis facing our environment and human health. Human inhalation or ingestion of microplastics that accumulate over time — including from our food supply; think shrimp and vegetables whose oceans and soil are polluted with microplastics and microfibers — can lead to organ damage, endocrine system dis-orders with negative reproductive and metabolic repercussions, and may even increase the risk of cancer.

Interest In Natural Options

Considering the growing number of microplastics studies and major concerns for the global ecosystem, there is renewed interest in natural components. Likewise, natural fibers are highlighting just what it means to be natural. Two such campaigns are the “Plant Not Plastic” — plantnot plastic.org — and “Make the Label Count” — makethelabelcount.org. The “Plant Not Plastic” campaign, launched by the National Cotton Council of America in response to the findings from its “Microplastics

Corporate Strategy & Insights Consumer Survey,” is a public awareness campaign with a goal of educating consumers on the positive contributions they can make to the environment and human health by choosing clothing and home textiles made from natural fibers. The campaign has taglines like: “Plant, Not Plastic,” “What You Wear Matters,” “Choose Cotton — the natural choice to protect your family and y(our) home.”

While consumers have increasingly moved away from checking labels and have shown less interest in fabric content, the highlighted risk posed by choosing synthetic textile goods is likely to cause a significant change in behavior.

Speaking of labels, the “Make the Label Count” coalition’s work is aimed less at consumers and more at European Commission regulators who are responsible for establishing a standardized life cycle assessment method for measuring and communicating the products and services Product Environmental Footprint (PEF). Under EU regulations, products must be assigned a PEF to enable fair comparisons to be drawn between products when comparing their holistic environmental impacts. The international coalition, made up of natural fiber organizations and environmental groups, has been successful in convincing the European Commission that its preliminary PEF methodology for apparel and footwear has several omissions including microplastic release. Further, the coalition argues plastic waste generation, and the circularity of materials should be accounted for in the PEF.

Cotton Versus Plastic

Cotton wins when it comes to microplastics. It is that simple. Cotton is a naturally occurring plant that grew on earth’s trees, fell onto its soil, and was disposed of by natural biodegradation long before it clothed its inhabitants. In its natural life cycle, carbon dioxide simply moves back and forth from the atmosphere to the plant and then back into the atmosphere.

Some in industry and science want to make the argument that dyed and treated cotton fibers are no longer biodegradable. The dyes and treatments might not be biodegradable, but that’s a small fraction of the fiber’s weight. Comparatively speaking, neither the synthetic microfiber nor the dyes and chemicals in it are biodegradable. But, for cotton to be a viable replacement for brands, retailers, and consumers looking to reduce their microplastic risk, it cannot check only that box, other boxes also matter.

Full Circularity?

End of product life is another critical factor for our industry to consider. Cotton fiber is already more circular than polyester and has great potential to become even more so thanks to the research and innovations occurring within many public and private organizations including Cotton Incorporated, the Cary, N.C.-based not-for-profit research and promotion company for U.S. upland cotton which is funded by U.S. cotton growers and importers. The U.S. cotton industry is incessantly working on ways to keep the carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere by the growing cotton plant and stored in its cellulose out of the atmosphere permanently, or at least temporarily, to help lower the textile industry’s carbon footprint.

Examples include compost, biochar, and mechanical and non-toxic chemical recycling and repurposing. Products labeled as “recycled polyester,” are not a polyester-to-polyester product, and it still contributes, perhaps even disproportionately, to the microplastic and land fill problems. If the two fibers are incinerated, cotton simply releases the carbon dioxide it absorbed during photosynthesis while polyester releases multiple toxic gases that are ultimately a source of new, man-made carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Responsible Practices

And, of course, trust in the fiber production system is especially important to brands and retailers. U.S. cotton farmers use advanced, responsible production practices and many are choosing to take the extra step to document what they are doing using practice verification programs like Better Cotton, Regenagri, and the U.S. national sustainability program the U.S. Cotton Trust Protocol (Trust Protocol). These programs are not only third-party practice verification programs, but are also a source of transparency, production metrics, and, perhaps most importantly, traceability back to country of origin. Just like cotton farmers, these programs are constantly evolving and increasing the value they offer to the supply chain.

Once such example of evolving program offerings is the Field Partner Program pilot launched by the Trust Protocol. This program allows merchandiser organizations with proprietary regenerative practices programs to partner with the Trust Protocol to provide brands and retailers with regenerative cotton via the program’s existing infrastructure. The standard Trust Protocol verification process is augmented with advanced satellite imagery analysis to validate regenerative practices.

The Trust Protocol has identified minimum requirements for the Field Partner Program based on regenerative agriculture frameworks from leading organizations. The practices observed and measured impact soil health, water use, synthetic inputs, water quality and biodiversity. The Field Partner Program is just one example of what the U.S. cotton industry is doing to make sure cot-ton fiber is a viable, desirable, and safe choice for brands, retailers and consumers.

Buying American Cotton Act

Increasingly, brands and retailers are going to be looking for natural fiber alternatives as they respond to regulatory and consumer concerns over synthetic fibers. The U.S. cotton industry’s number one legislative priority right now is a federal tax incentive that would provide a financial incentive to make that transition to U.S. cotton easier. The Buying American Cotton Act (BACA), introduced in May 2025 by Mississippi Senator Cindy Hyde-Smith, would allow entities selling finished products in the U.S. retail market to claim transferable tax credits if they are able to demonstrate proof of the use of U.S. cotton in those products. The tax credit that may be taken depends on the price of cotton as established by the U.S. Treasury, the weight and type of U.S. cotton contained in the finished good — raw cotton, yarn, or fabric —and where the finished product was manufactured. U.S. manufactured yarns and fabrics’ raw cotton weight multipliers of 1.6 and 6.5, respectively, are applied in the case of U.S. cotton value added products. The final tax credit calculated for the product is determined by multiplying by a location factor of 24 percent if the good was made in the United States, or a country with which the United States has a free-trade agreement; otherwise, the location factor is 18 percent. For example, a product made in Pakistan imported for sale in the U.S. retail market that contains a pound of U.S. cotton valued at $0.85 per pound (lb). would be accompanied by a transferable tax credit of $0.15 when the applicable cotton price is $0.85/lb — $0.85 x 1 lb x 0.18 = 0.15. This credit will go a long, long way to increasing U.S. cotton’s competitiveness at U.S. retail compared to other non-U.S. cotton fiber choices.

Given all that is happening with the microplastic crisis in the world and textile waste, it is time for the global textile value chain to revisit its reliance on man-made fibers and move to a responsible natural solution. Sourcing professionals will do well to give U.S. cotton and all it has to offer a closer look.

Editor’s Note: Hank Reichle is president and CEO of Staplcotn, the oldest and largest cotton cooperative in the United States headquartered in Greenwood, Miss. He also serves as an officer of the National Cotton Council and as a director for the U.S. Cotton Trust Protocol.

2025 Quarterly Issue IV