T

he increasing focus on the well-being of planet Earth has engendered concerns about what

effects many products might have on the health of consumers and the planet alike, as well as new

expectations with regard to what goes into the making of those products. Consumers are making it

known that they want products that do not have deleterious effects on the environment, in their

making or their use or their disposal. Partly in response to these expectations, partly out of

their own sense of responsibility, and partly out of a realization that it is economically

beneficial to do so, certain manufacturers are taking steps to reduce the environmental impacts of

their products; and they want to make sure consumers know about their efforts. Other manufacturers

are looking for aspects of their products that they can market with any sort of environmentally

friendly association – whether there is a clear connection or not – in a “greenwashing” effort to

leverage the current eco-sensitivity to their advantage.

As a result, the consumer is receiving messages left and right touting products’

environmental integrity. Marketing materials are full of words such as “green,” “eco-friendly,”

“sustainable,” “renewable,” “recyclable,” “organic” and a host of other related terms. The claims

may not always provide a clear picture of the product’s true environmental impact because the terms

may be used in such a general way as to have no certifiable meaning but rather convey simply an

idea of environmental responsibility; or they may relate to one aspect of a product – for example,

a 100-percent organic cotton garment – while another is clearly not environmentally friendly – that

garment has been dyed using toxic dyes in a process that pollutes the river into which the plant

releases its effluent. If marketing claims cannot be substantiated or are not qualified, or if they

are shown to be deceptive or misleading, that greenwashing has the potential to cause consumers to

become skeptical or, worse, tune out the message altogether when valid claims are made for other

products.

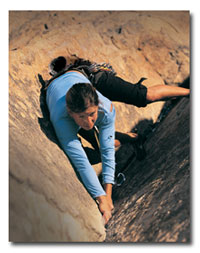

Outdoor apparel marketer Patagonia’s Common Threads Recycling Program takes back worn out

Capilene® base layers and other used clothing to recycle into new garments.

Photo courtesy of Patagonia Inc.

FTC Green Guides

In a move to address green marketing issues, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) developed

its “Guides for the Use of Environmental Marketing Claims,” also known as the Green Guides, to

provide a framework for voluntary compliance with FTC regulations related to environmental

marketing and advertising practices. First published in 1992, the guides were last reviewed in

1998. With the recent onslaught of green marketing claims, particularly with regard to textiles and

building, the FTC is now considering further revisions, and over the past year has held a series of

workshops to educate the public about the various issues surrounding such claims and receive input

to help it in making the revisions.

The general principles set out in the original Green Guides apply to all green marketing

claims and stipulate that these claims, whether specific or implied, must be substantiated or

qualified in a way that consumers can understand. The guides also provide examples of general and

specific claims to illustrate comparative degrees of clarity or accuracy.

The textile-related portion of the FTC’s workshop titled “Eco in the Market – Green Building

and Textiles,” held in July of this year, brought together representatives of Organic Exchange,

Cotton Incorporated, North Carolina State University, US Customs and Border Protection, the Organic

Trade Association (OTA), outdoor apparel marketer Patagonia® Inc., The Good Housekeeping Research

Institute and Consumer Reports to share their knowledge and ideas about what is and isn’t green and

propose parameters for FTC guidance regarding marketing and labeling of green textiles.

Degrees Of Green

As was pointed out at the FTC workshop, there are varying degrees of green in different

textile products. In some, the materials used may be green, but the manufacturing process may not

be, or vice versa; and marketers need to be clear as to which aspect of a product a green claim

applies. For example, the National Organic Program stipulates that a textile containing a blend of

organic cotton and another material, such as spandex or nylon, must state all of the components and

not just the cotton content.

As another example, one also must be careful when making claims for a product that contains

a blend of organic, biodegradable cotton and recycled polyester in a single textile article. While

each fiber may be sustainable on its own, another issue crops up when they are combined either in a

single yarn or as separate yarns woven into one fabric: It can’t completely biodegrade because of

the polyester content, and it can’t be recycled in a cradle-to-cradle polymerization process

because of the cotton content. It could be cut into strips and used in another textile, say, a rag

rug, or repurposed in some other way, but it still will eventually enter a noncompostable waste

stream. In such a case, the green credentials of the materials can be touted, but biodegradability

or recyclability claims could not be made for the end product unless the two materials can be

separated to go into the relevant downstream processes.

As another, not entirely unrelated, issue, can the same performance claims be made for a

regenerated cellulosic fiber as for the raw fiber from which it is derived? This question has come

up in the case of bamboo, a renewable, fast-growing resource that needs little water and no

pesticides for its cultivation. The raw fiber has antimicrobial and moisture-transport performance

properties, and these properties are claimed for many of the apparel products currently offered on

the market. But, according to workshop presenter Dr. Peter Hauser, NCSU, while these properties are

retained in bamboo that has been processed mechanically similarly to the processing of flax into

linen, it is unclear that they are retained in the more commonly used regenerated solvent-spun

fiber, which is essentially either a rayon fiber – whose chemical-laden processing raises

environmental issues – or a lyocell fiber – which is made using a recoverable and reusable solvent

in a sustainable closed-loop process. Hauser stressed the need for scientific peer-reviewed

documentation of any claims regarding fiber performance. His call was backed up by presenters

Kathleen Huddy, The Good Housekeeping Research Institute, and Pat Slaven, Consumer Reports.

Third-Party Certification

Companies may have their textile products and processes evaluated and certified for their

environmental integrity by a third-party agency such as MBDC; Switzerland-based International

Oeko-Tex Association; Switzerland-based bluesign technologies ag; the International Working Group

of Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS), a group comprised of OTA and three other associations

promoting the use of organic raw materials; and other agencies. Such certifications serve to assure

consumers that green marketing claims made for those products are valid.

The Oeko-Tex® Standard 100 certifies that textiles from raw materials through end product

comply with prohibitions and regulations regarding the presence of harmful substances, as well as

with criteria related to substances known to be harmful to human health but not yet regulated, and

with other parameters related to colorfastness and pH value. Oeko-Tex also offers a Standard 1000

to certify compliance by manufacturing plant operations with environmentally responsible production

parameters.

MBDC’s Cradle to Cradle Design Protocol and the bluesign® standard encompass, each in one

certification, the entire supply chain and all manufacturing processes that go into a product. All

materials going into a product – fibers, yarns, dyes, chemicals and other components – plus

manufacturing parameters – energy and resource usage, wastewater management, plant emissions,

employee health and safety, and other parameters – are evaluated, and products are certified at set

levels based on the degree of optimization. Both organizations work with clients to help them

design out of their products substances and practices that are harmful to the environment and human

health, and incorporate the most environmentally beneficial alternatives and solutions possible.

GOTS encompasses the production, processing, manufacturing, packaging, labeling and

logistics-related aspects of organic textiles from fiber through end product. Certified products

may be labeled in one of two ways: “organic” or “organic – in conversion,” for products containing

at least 95-percent certified organic or in-conversion fibers; and “made with x-percent organic

materials” or “made with x-percent organic – in conversion materials,” for products containing 70-

to 95-percent or more certified organic or in-conversion fibers.

Transparency Is Key

Ventura, Calif.-based Patagonia has long been committed to environmentalism, from its

sensitivity to the impact of its products on the environment and its commitment to foster the

well-being of the people producing them as well as its direct employees; to building its own solar

collection system to help power its headquarters and implementing other earth-friendly measures in

Ventura and at its LEED-certified distribution center in Reno, Nevada; establishing a

garment-recycling program to take back worn garments for reprocessing into new ones; and giving

back a percentage of its profits to environmental causes; among other measures. The company’s

website offers extensive information about its environmental commitment, including analyses of the

environmental footprints of a number of its products.

In order to promote its eco-textile program, Patagonia labels products with a green E when

they contain at least one-third by weight of what it considers environmentally friendly fibers. The

company also includes additional information about the labeling in its stores and catalogs.

The fibers that qualify for this designation include organic cotton, hemp, chlorine-free wool,

recycled polyester, recycled nylon and Tencel®.

In 2007, Patagonia became the first brand globally to become a member of the bluesign

standard. As a brand member, it has committed to promote implementation of the bluesign standard

throughout its supply chain.

Rob BonDurant, Patagonia’s vice president of marketing, speaks to the need for transparency

in green marketing: “If green marketing is a first step for a company, we believe it’s a good first

step in the right direction. Eventually, customers are going to want to know the specifics behind a

company’s green marketing claims – and companies will be either inspired or literally driven

towards making changes in the way they do business. At Patagonia, we believe that transparency is

key. Corporate honesty begets customer loyalty. When a customer knows they can come to you to learn

about where your product came from, who made it and what it’s made of – everybody wins.”

What Is Green?

Green connotes the general idea that a product or a process is beneficial to, or at least

has minimal impact on, the environment with regard to energy, resource and raw material usage;

greenhouse gas and toxic emissions; and/or waste generation. It often is interchangeable with

environmentally friendly, eco-friendly and other general terms.

Sustainable is a broader term that encompasses not only the environment, but also economic

and social equity considerations. A sustainable product has minimal impact on the environment in

that harvesting or resource usage does not deplete or permanently damage the resource; plus, it can

be produced in an economically viable way and it is produced with consideration for the welfare of

employees and others impacted by the production.

Cradle-to-cradle refers to a regenerative life cycle in which no material making up a

product becomes waste because noncompatible materials in the product can be separated and all can

be recycled and reused for the same purpose as the original virgin material. This is in contrast to

a cradle-to-grave product that cannot be recycled and ends up in a landfill at the end of its

useful life, or a cradle-to-gate product whose environmental footprint has been calculated from raw

material acquisition through the manufacturing process.

The term “cradle to cradle” was coined by Charlottesville, Va.-based McDonough Braungart

Design Chemistry LLC (MBDC), a design consultancy that advises companies in the area of what it

calls eco-effective product design, taking into account all aspects of production and material use.

MBDC also is a third-party certifier, using its Cradle to Cradle Design Protocol to assess

materials and processes according to environmental and human health criteria.

As noted elsewhere, there are numerous other terms as well that are used in describing a

product’s and process’s environmental integrity or function.

The Greening Of The Cotton Supply Chain

A video produced by Cotton Incorporated examines new processing technologies that are

significantly improving the sustainability of the entire supply chain for cotton products. While

cotton cultivation practices have improved vastly in recent years, including the development of

varieties that have increased yields and require far less chemical and water input, new dyeing and

finishing technologies also require fewer chemicals and consume less energy and water while also

releasing cleaner effluent. Process technologies highlighted include new enzymes and ozone

technologies that replace harsh chemicals in fabric finishing, very low-moisture foam dyeing

technologies, waste- and solvent-eliminating digital printing technologies, low-salt reactive dyes,

bleaching processes that drastically reduce water and energy use, and technologies that combine

dyeing and finishing in one step, among other technologies. The video also presents the point of

view of respected retailers who expect

manufacturers to implement these new green technologies as a prerequisite to a continuing

business relationship.

The video, “Textiles: The Sustainability Revolution,” can be viewed at

www.textileworld.com/video/cotton.html

November/December 2008