Add Value Or Else

A Caribbean Basin Initiative strategy for U.S. mills Despite all the high hopes and

hoopla surrounding the passage last year of the Caribbean Basin trade legislation, the results,

thus far, have been disappointing for most U.S. mills producing apparel fabrics or yarns. There is

little doubt that imports of apparel products from the region will grow over the next few years.

The real question is whether the Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI) region can compete in the long

term with other apparel-producing regions especially after the quotas are removed on apparel

imports from other countries in 2005.For producers of apparel fabrics and yarns, this situation is

particularly critical. Like it or not, U.S. apparel production will continue to decline, and

imports of finished garments will continue to increase. Even the most competitive U.S. producer of

apparel fabrics or yarns will find it hard, if not impossible, to prosper without a competitive

downstream customer.The other cold reality is that retailers and wholesalers of apparel products

will always be forced to chase the cheap needle. And even though labor costs today are considerably

lower in the CBI region than in the United States they are still considerably higher than in other

less-developed countries in Southeast Asia, the Indian Subcontinent and Africa.

Elimination Of Quotas Will Reduce CBI AdvantageBy far, the biggest and most important

advantage for the CBI region is in the zero-duty rate on qualifying garments, i.e. those made from

U.S. fabrics and yarns. Currently, that advantage is significant in many key product

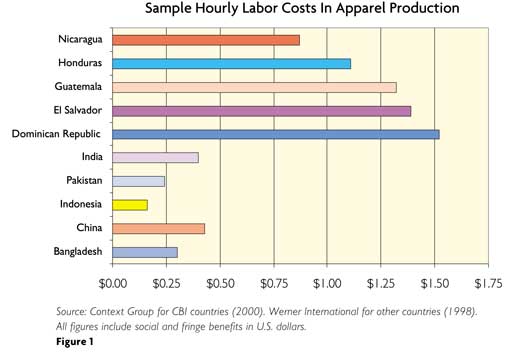

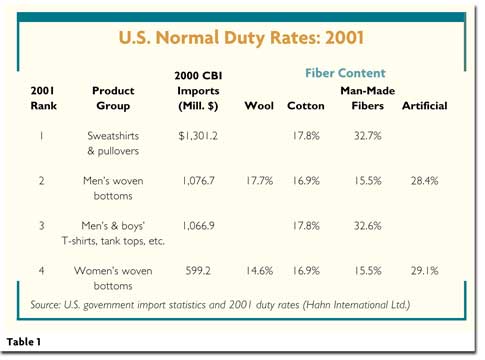

classifications when compared to the duty rates on imports from Asia and other regions.Figure 1

shows the top imports from the CBI region in 2000 and the duty rates that would apply to the same

garments imported from China, India or most other countries.Unfortunately for the CBI region (and

Mexico), the elimination of import quotas (not duties) on other countries in 2005 will cut deeply

into that competitive advantage.For most imports still covered by U.S. quota restrictions and that

includes most apparel products there is frequently a cost associated with acquiring the export visa

in the supplier country. The quota cost if there is one is usually reflected in the f.o.b. cost of

the garment from the foreign manufacturer. The cost of quota can vary significantly from country to

country, depending on U.S. market demand for the product, the capabilities of manufacturers in a

particular country, and the quantity of quota available in that country for that quota year. Quota

costs also rise and fall during the quota year.In some countries such as Hong Kong and China the

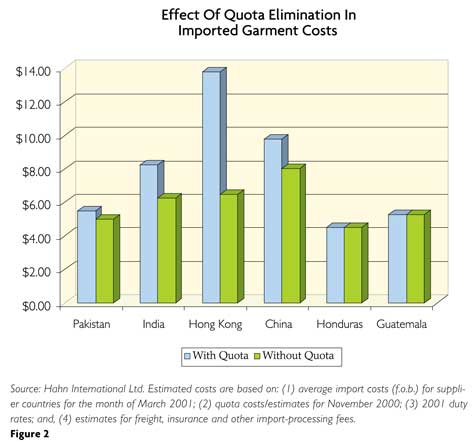

quota charge can be significant.Figure 2 illustrates the before and after impact of the elimination

of import quotas on one important product classification mens cotton polo shirts.Its clear from

this example that factories producing polo-style shirts in the CBI region could easily find

themselves after 2005 at a competitive disadvantage with producers in lower-cost countries such as

Pakistan and for moderate- to better-quality polo shirts from countries such as Hong Kong, China

and India. The same, of course, applies to other products as well.

CBI Region Lacks Packaging Infrastructure Or FacilitatorsAnother challenge facing the CBI

region is the growing demand for full-package garment production from U.S. wholesalers and

retailers. Unfortunately, few independent garment factories in the region have the capability to

offer full-package services due to financing limitations, lack of knowledge about U.S. fabric and

trim sources, inadequate pattern-making or fabric-cutting capabilities, and other critical elements

of full-package production. Likewise, few independent factories in the region can offer the type of

product development support or quick turnarounds on samples or pricing as can their Asian

competitors.While there are some U.S. companies such as Perry Ellis International, VF Corp.,

Kellwood, Tropical Sportswear and others that can effectively facilitate or manage full-package

production in the region, theres room for more. Although the Asians are well-represented with

factories in the region, most of the fabric and trim purchasing and other coordination/facilitation

is done through their Asian offices which puts U.S. mills at a disadvantage.The situation begs for

more facilitators or aggregators to step in and fill this role. The recent formation of the

Amerisource Group is a step in the right direction. Hopefully, for U.S. mills, others will

follow.

Long-Term Strategy: Add ValueFor the short term, U.S. producers of apparel fabrics and yarns

have little choice but to focus on those product groups in which North American producers are

currently the most competitive bottom-weight cotton fabrics and basic cotton knits for T-shirts,

sweatshirts and underwear. However, for the longer term, U.S. mills are going to need a different

approach in order to prosper.1.Focus on higher-value fabrics.With CBI labor costs already high in

relation to other lower-cost countries such as Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, its critically

important for the long term to reduce the labor-cost component in garments produced in the region

without lowering the value of the product. The best way to do that is to increase the value of the

fabric in the garment.Finding ways to increase the use of better-quality wool and synthetic fabrics

in mens and womens dress slacks would be one example of a strategy that could work for the

region.2.Forge alliances with best-of-class knitters and finishers.The lack of knitting capacity in

the CBI region is proving to be a real obstacle for U.S. yarn spinners. Yarn spinners should be

forging alliances with top-quality U.S. knitters to do full-package production of better-quality

knit garments in the CBI region, or else looking for an Asian partner that is willing to build a

knitting plant in the region. Likewise, U.S. greige weavers need to partner with best-of-class U.S.

finishers to produce better-quality bottom-weight or shirting fabrics.3.Upgrade the capabilities of

CBI factories.Using the best fabrics alone will not be enough if the CBI region cannot meet the

quality standards or price points of U.S. retailers and wholesalers. Just looking at the list of

top imports from the region, one sees the current focus on basic, relatively low-labor-content

products like T-shirts, jeans and underwear. Unless factories can upgrade their sewing skills and

productivity over time, they will be displaced by new low-cost suppliers in other regions.U.S.

mills need to be identifying and partnering with factories in the region that have the will and the

resources to upgrade their capabilities. In many cases, these will be Asian-owned plants with

headquarters in Asia. Calling on those factory owners should be a top priority. Making the economic

case for the use of U.S. fabrics in CBI production will also be required.4.Find the

aggregators.Likewise, U.S. mills need to be forging alliances with U.S. and Asian aggregators doing

production in the CBI region. These companies can bring the essential sourcing network, logistical

and financing capabilities, product development support, and most importantly the customers to the

table.5. Develop product sourcing infrastructure and outsourcing capability.Last but not least,

U.S. yarn spinners, knitters and weavers should not put all of their eggs in the CBI basket. While

the CBI region and Mexico can provide economical alternatives to U.S. apparel production, the

strict rules of origin requiring the use of U.S. fabrics and yarns can be both a blessing and a

curse. In order to reduce costs, move up the value chain and meet the future needs of U.S.

retailers and wholesalers, U.S. mills are, in some cases, going to have to supplement their use of

local yarns and fabrics with imported products.Using imported yarns, however, does not necessarily

rule out the possibility of lower-cost apparel production in North America. Under NAFTA rules, sewn

product assembled in Mexico can still qualify for full NAFTA benefits zero duties and no quotas as

long as the fabric is formed and cut in the U.S. This rule creates opportunities to use imported

yarns to upgrade a knit or woven fabric and still meet the pricing requirements of a U.S.

wholesaler or retailer.

Editors Note: Jim Langlois is executive director of Hahn International Ltd., Stamford, Conn, a

company that helps its industry clients develop and execute strategies to stimulate growth and

profitability in the North American market.Hahns team of senior professionals and strategic

alliances with other industry specialists bring strategic planning, market research methodologies

and access to top executives throughout the fiber, textile, apparel and retail supply chains. The

company has extensive hands-on experience in production, marketing, importing and exporting of

textile-related products. For more information visitwww.hahninternational.com.

October 2001