Contech PresentsNew Slitter/Sheeter SystemContech, Goddard, Kan., offers a new roll-fed slitter/sheeter system that uses a shaftless unwind to permit quick changes of rolls of material weighing up to 8,000 pounds.After slitting, the material is gathered through controlled gravity loops that restrict material stretch and cut using a gap shear cutter. The sheets are then grabbed and stacked using a gripper stacker. July 2002

Melco Introduces Amaya Embroidery System

Melco IntroducesAmaya Embroidery System

Melco Embroidery Systems, Denver, a wholly owned subsidiary of Saurer Ltd., Switzerland, reports its Amaya embroidery machines are the first to provide modular capabilities. Amaya offers flexible configuration of up to 30 heads, with the possibility of operating multiple units simultaneously from one PC computer.Other features include automatic Acti-Feed Thread Tensioning, consistently high speeds of up to 1,500 stitches per minute, 16 needles per head, laser tracking, a built-in tutorial system, adjustable pressure foot, new safety grabber and more.July 2002

I N C Materials Installs Struto Releases Deci-Tex

I.N.C. Materials InstallsStruto®, Releases Deci-TexAustralia-based I.N.C. Engineered Materials recently added Struto® vertical lapped nonwoven fiber technology to its existing lamination and adhesive backings equipment.Following research and development efforts using the new equipment, I.N.C. has introduced its new Deci-Tex 3D materials. Selected for use by three Australian car makers, Deci-Tex offers 50 percent higher sound absorption and is 75 percent lighter than traditional felts used by auto makers, according to I.N.C. The Struto technology was developed by a company in the Czech Republic and is available in the United States through Dalton, Ga.-based Georgia Textile Machinery.June 2002

Textiles In Stitches

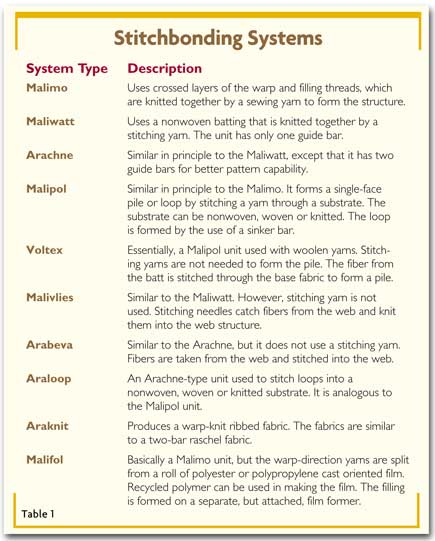

By Richard G. Mansfield, Technical Editor Textiles In StitchesStitchbonding is finding its niche after years of trial and error. Stitchbonding is a hybrid technology using elements of nonwoven, sewing and knitting processes to produce a wide range of fabrics that are used in home furnishings and industrial fabrics, including composite structural applications. The versatility of stitchbonding can best be understood by reviewing the types of stitchbonding processes (See Table 1).The initial work on stitchbonding took place in Czechoslovakia and East Germany during the 1960s using short-staple fibers to produce fabrics for industrial and utilitarian non-styled household uses. These fabrics were made using creel-fed, spun stitching yarns. As the use of stitchbonding spread to the United Kingdom and other countries, nylon and polyester filament yarns became the preferred materials for the stitching component. Malimo Stitchbonding SystemsThe Mali system of stitchbonding was initiated during the late 1940s by Heinrich Mauersberger of East Germany. His U.S. Patent #2,890,579 was issued on June 16, 1959. Mauersbergers first fabrics were based on joining warp and filling yarns with a stitching yarn to produce a woven-like fabric. The first product produced by the Malimo stitchbonding process was a toweling, made in 1952. To introduce the Malimo machine in the United States, the East German manufacturer appointed Klauss Bahlo to be its manufacturers representative in the United States. When CromptonandKnowles Co. took a license from the East German manufacturer of the Malimo around 1962, Bahlo became a vice president with the company. CromptonandKnowles imported a number of machines to the United States.

Karl Mayer’s Malimo machine is used for the stitchbonding of multi-layer reinforcement fabrics for the composite industry. The first two Malimo units went to Guilford Woolen Mills in Guilford, Maine. Guilford was then run by King Cummings. The companys initial efforts with the Malimo machine were concerned with the use of woolen yarn. By mid-1963, Cummings decided to sell development time on the companys Malimo machines to other textile companies, rather than trying to develop fabrics for Guilford. Indian Head Co. became interested in the Malimo machine and ran extensive trials on the machinery at Guilford. Indian Heads decision to put the Malimo in a knitting plant was based on its experience gained from using the machines at Guilford.In March 1963, Indian Head ordered two Malimo units at a price of $45,000 per machine. Four months later, Indian Head set up the first Malimo machine at its Native Lace Co. plant in Glen Falls, N.Y. Dan Duhl, who later was to become president of the Polylok Corp., was appointed product development manager for the Malimo program in April 1964.Initial trials by Indian Head with the Malimo used a range of materials including mohair, worsted and cotton novelty yarns. A considerable number of mechanical problems were encountered with the early Malimo machines. Fabric problems included curling selvages, side-to-side nonuniformity and mending problems.As development work at Indian Head progressed with the Malimo fabrics, home furnishings fabrics were recognized as having good potential. The first production order by Indian Head was a drapery fabric using a preshrunk polyester stitching yarn combining a random warp of cotton and a filling of natural and yarn-dyed cotton and rayon. Another drapery fabric produced by Indian Head was a fabric known as Fiberglo. This fabric was made of modacrylic, rayon and polyester fibers and had excellent flame-resistant properties.A number of promising fabrics for casements, draperies, reinforced industrial fabrics and coating substrates were developed by Indian Head from the start of its program in 1963 until its termination in 1973. One of these fabrics was a cold-weather apparel fabric called Thermal-Dermal made by stitching yarn into polyurethane foam.Indian Head, as a $400-million conglomerate, did not want to absorb further losses on the Malimo program. The establishment of the Polylok Corp. by Duhl provided a good mechanism for Indian Head to terminate the project. The machinery was sold under very favorable terms to Polylok, which allowed Duhl to start a business with a relatively small initial capital outlay. Other Mills That Worked With The MalimoBurlington Industries, Greensboro, N.C., put a considerable amount of effort into the Malimo system over about a four-year period. It established a separate Nexus Division for the Malimo program, developing a number of casement and drapery fabrics. A line of tablecloths was developed and marketed through Sears and other chain stores. Burlington unsuccessfully tried to develop womens- and menswear fabrics with the Malimo. The womenswear fabrics were based on woolen spun yarns, and the menswear fabrics used worsted yarns. One of the major shortcomings of the Malimo fabrics for apparel use was their lack of recovery when deformed; garments would bag at the elbows and knees.In early 1969, Burlington announced the division was closing, and activities with the Malimo machines were terminated. Both J.P. Stevens and M. Lowenstein also were unsuccessful in their efforts to develop apparel fabrics using the Malimo machine. Reeves Brothers was interested in Malimo fabrics because of their high tear strength and dimensional stability. However, in comparing the Malimo substrates to woven fabrics for coatings, at that time it found that no cost savings were obtained with the Malimo fabrics.Libbey Manufacturing in Lewiston, Maine, under the direction of President Paul Libbey, entered the stitchbonding business in the late 1960s using Malimo and Maliwatt machines. Libbey produced Malimo casement fabrics for the home decorating trade, and industrial glove and shoe linings using Maliwatt equipment.

Why Did Malimo Have Only Limited Success In The U.S.Stitchbonded nonwovens gained acceptance in Europe, particularly in the Soviet-dominated Eastern-Bloc countries, where fabric aesthetics were not a major concern. Later, acceptance of stitchbonding grew gradually in Western Europe for specialty fabrics. By 1984, there were more than 1,000 machines producing more than a billion yards of fabric per year. Most of these machines were producing industrial fabrics.The Malimo achieved success in home furnishings and domestics in the United States, where the unique appearance of the fabrics was a virtue. Included were fabrics for casements, draperies and tablecloths. In industrial fabrics, the Malimo has been used successfully to make substrates for coated abrasives and in conveyor-belt applications in which extreme dimensional stability is important. Polylok, Tietex and Superior Fabrics were able to develop Malimo fabrics for vertical blind louvers.A major factor in the disenchantment with the Malimo was that it was oversold to the textile industry as a high-speed replacement for the loom. Raw materials for fabrics produced using the Malimo cost as much as or more than raw materials used for woven fabrics, because a three-yarn system is used and the quality of the stitching yarn is very important. Direct costs for the Malimo are higher than weaving because one worker can attend only about five machines, while a worker can attend more than 100 looms. The stitchbond machines produced in the Soviet-Bloc countries suffered from lack of quality control in their manufacture and required extensive maintenance work to keep them running Tietex Co.Tietex Co., Spartanburg, is the most successful stitchbonded nonwovens company in the United States and the worlds largest producer of stitchbonded fabrics. In addition to Malimo machines, Tietex has Liba stitchbonding machines. The company was started in 1972 by Arno Wildeman. Wildeman had been associated with Cosmopolitan Textiles of England, a producer of stitchbonded fabrics used for printed drapery and bedspreads. Wildeman developed techniques for modifying the machines he purchased to make them more reliable and versatile. One of his patented developments was a method of locking in the tricot stitching in a Maliwatt-type machine by tying in the stitching yarn to the fleece fibers.Tietex diversified its product line and soon added mattress ticking and flexographic printing. Tietex is believed to be the only major company using flexographic printing for textiles. Up to eight colors can be applied on this unit. One of the major advantages of flexographic printing is that it requires less dyestuff to produce a shade than it would to print the same pattern and shade using rotary screen printing or roller printing.The company has developed techniques for foam finishing and foam application of coatings to its stitchbonded fabrics. The foam application of finishes to prevent pilling has been an important factor in expanding the companys range of products. Tietex also has developed 44-gauge stitchbonding equipment.Tietex now has the most diversified range of products in the stitchbonding business. Home furnishings products include mattress ticking, bedspread and drapery fabrics. The development of the stitchbonded mattress ticking by Tietex virtually eliminated the osnaburg cotton ticking from the market. Expansion And Diversification By TietexAfter the sudden death of Arno Wildeman, his son Martin took over the reins of the company and continued to expand and diversify the company in accordance with his fathers long-range plans. The company has expanded its Thailand-based plant, Tietex Asia Ltd., which was built in 1997. Some of the output of the Thailand plant is sold in Asia for use in footwear, hunting and recreational products. The company now is considering building a plant in Poland in order to better serve the European market.Recently, the company has developed a line of stitchbonded upholstery fabrics. An affiliated U.S. company, Interflex Laser Engravers, Spartanburg, produces flexographic printing rollers for Tietex, as well as rollers for flexographic printing of film and other materials for the packaging industry. New Techniques For Stitchbonding

Karl Mayer’ latest machine, the Multiknit, produces fabric with a double-sided knit effect.Karl Mayer of Germany has modified the basic Malimo technology to produce three-dimensional fabrics. Using these techniques, fabrics can be produced that have low specific weight, good compressive elasticity and moldability, and possible use as polyurethane foam replacement in automotive and other seating uses.The Kunit three-dimensional fabrics made of staple fibers are comprised of one stitch side and one pile loop side that has an almost vertical fiber arrangement. The lengthwise-oriented fibrous web is folded and compacted into a pile fiber web at high speed and supported by a brush bar. The fibers are pressed into needle hooks by the brush bar to form a stitch. In the Multiknit system, a fleece fabric with plain stitches on one side that has been made by the Kunit process is used as the Multiknit base fabric. The double-sided knit effect of the Multiknit fabric is produced by forming the fibrous content of the pile folds into loops to produce the second knit surface. The Outlook For StitchbondingThe growth in stitchbonded fabrics will be relatively modest in home furnishings and more conventional types of industrial fabrics. The greatest potential will be in fabrics for composites and fiber-reinforced polymers (FRP), and in products to replace polyurethane cushioning in automotive and furniture seating. The availability of stitchbonding equipment from a high-quality and development-oriented company like Karl Mayer should also be a key factor in the growth of these newer applications.June 2002

QuikWater Heaters Provide Clean Efficient Operation

QuikWater Heaters ProvideClean, Efficient OperationRecent tests reveal the Ultra-low NOx direct contact water heater from the QuikWater Division of Tulsa, Okla.-based Webco Industries Inc. produces NOx emissions of 9 parts per million or less without using external controls, while maintaining 99-percent thermal efficiency.The heaters consume energy only when hot water is being used. A patented dry firing chamber permits complete combustion, and fuel savings of up to 50 percent are possible, according to the company.July 2002

Debate Begins On Textile Tariff Cuts

T

he opening salvos have been fired in what will be a months-long battle over whether and

how much to cut textile and apparel tariffs during the current round of global trade negotiations

by World Trade Organization (WTO) members.

U.S. Trade Representative Robert Zoellick asked the U.S. International Trade Commission to

conduct hearings to assess the probable economic impact of tariff reductions on U.S. industries.

On the basis of information gained, he will make recommendations to President George W. Bush

this month with respect to the U.S. negotiating position.

At the commission’s recent hearing, Charles V. Bremer, vice president for international

trade at the American Textile Manufacturers Institute (ATMI), said the textile industry “cannot

countenance or withstand” any further tariff cuts.

He added, “It simply is unthinkable for the United States to grant further tariff

concessions to countries which have not even lived up to their Uruguay round of tariff and trade

bargains.”

On the other hand, Brenda Jacobs of the U.S. Association of Importers of Textiles and

Apparel said high tariffs do not protect U.S. industries from competition, and they add to the cost

of consumer products.

Jacobs said the United States should not “unilaterally disarm,” but the trade talks should

result in reciprocal reductions of tariffs and other trade barriers.

Administration Hangs Tough On Strong-Dollar Policy

Treasury Secretary Paul H. O’Neil has made it crystal clear that the Bush administration has

no intention of altering its policies supporting a strong dollar, a position that U.S. textile

manufacturers contend is having a devastating impact on business.

While admitting that some industries are hurt by the strong dollar, O’Neil told senators at

a recent Banking Committee hearing that he is much more concerned about the impact a weaker dollar

would have on consumer prices.

He told the senators, “I don’t know anyone who wants to reduce imports. If we take steps to

reduce imports, we become more of an isolated country and consumers pay more for their products.”

The strong dollar, which industry economists say is overvalued by about 30 percent, makes

imports cheaper and exports more expensive. This situation is contributing to a major increase in

the U.S. trade deficit.

A spokesman for a coalition of some 50 labor, agriculture and business trade associations

told the senators the overvalued dollar has resulted in the loss of 750,000 jobs in manufacturing

and farming, including 175,000 jobs in the textile industry alone.

They contend that the overvalued dollar amounts to a “30-percent tax” on U.S.-manufactured

goods, which cuts them out of markets at home and abroad.

Farm Bill Continues Cotton Competitiveness Program

The Farm Bill approved by Congress continues the textile industry’s coveted three-step

cotton competitiveness program through July 2006. The competitiveness program is designed to make

adjustments when the price for domestic raw cotton —which U.S. mills are required by law to use —

is higher than the world price.

Under the competitiveness program, the secretary of agriculture calculates the world price

for raw cotton. When the domestic price exceeds the world price, textile mills and cotton shippers

are paid the difference between the two prices. If the difference persists, mills are allowed to

import raw cotton.

Under the program, mills were required to pay the first 1.25 cents per pound of the subsidy,

but under the new legislation, that requirement is waived. U.S. manufacturers say the 1.25-cent

threshold puts them at a competitive disadvantage with overseas manufacturers and could cost as

much as $50 million annually.

June 2002

Currents Of Change

By Currents Of Change

Avondale Mills has become an institution in the textile industry, with a history spanning more

than 150 years. By the turn of the 20th century, as the South finally emerged from

reconstruction into the broad daylight of industrialization, a trio of companies had begun

operations in Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina. Avondale Mills, Walton and Monroe Mills and the

Graniteville Company, much like the three Fates of Greek mythology, were spinning and weaving

parallel threads of production, expansion and employee self-improvement in the early 1900s.A rich

heritage developed for all three companies over the ensuing century, one that was similar in its

focus on quality, value and opportunity. By the end of the 20th century, the companies, like the

fabrics they produced, had finally intertwined to form a cohesive whole.

The Birmingham Plant of Avondale Mills in 1897.

The original Monroe Mill in 1895.

The orginal Granite Plant, built in 1845. The formation of Avondale Mills, Inc., brought

with it the illustrious more-than-150-year history of these Southern companies, and it is from them

that the company takes its motto today: to develop partnerships through relationships, information

and product with its suppliers, associates and customers which create value and the opportunity for

each to grow and profit.Today, Avondale is one of the nations largest producers of utility-wear

fabrics, denim and sales yarn; and one of the largest consumers of cotton. With sales in excess of

$600 million, and more than 5,600 associates working in 20 plants in four Southeastern states and

15 sales offices across the globe, Avondale Mills continues the heritage of innovation that was

begun more than a century ago.How It All Began

The Graniteville Company was founded by William Gregg in 1845 in the Horse Creek Valley area

of South Carolina, producing fabric from locally grown cotton. Monroe Cotton Mill first opened

its doors in 1895, producing greige goods. The original directors included George Felker,

great-grandfather to Avondales current Chairman, President, and CEO, G. Stephen Felker.

The first Avondale plant opened in 1897 near the Avondale community of Birmingham, Ala., and

produced greige goods. Braxton Bragg Comer was the companys first president, later serving as

governor of Alabama and a U.S. senator.Walton Cotton Mill Co. began operations at the turn of the

century, opening its doors in 1901. It manufactured greige goods, and also was led by

Felker. The Early YearsWilliam Gregg chose to build the first Granite Mill from the areas

native blue granite, thus giving the mill, and later the town, their names. A strong proponent of

development in the South, Gregg believed that opening the mill would advance industrialization in

the area. He expanded production in 1880 and 1900, building two more mills. Granitevilles

founder would be pleased to know that Gregg Plant, which was named for him, is the largest

finishing plant in the world today.

Graniteville’s cotton fabrics were internationally acclaimed, even at the turn of the 20th

century. Walton and Monroe Mills, both built in Monroe, Ga., on opposite sides of the same

street, had their roots in the same investors. The original directors of the Monroe Mill and

original petitioners for the formation of the Walton Cotton Mill Co. included Billington Sanders

Walker, president of Monroe Mill; George W. Felker; Henry D. McDaniel; Coleman T. Mobley; and

George C. Selman.It was the common Board of Directors that allowed Walton Mill and Monroe Mill to

operate side-by-side as sister companies, becoming synonymous with each other over the years.By

1906, Walton Monroe had doubled in size. The companies were able to stay on top with investments in

current technology, again doubling in size in 1923.Avondale Mills had no less of an impressive

start, one that had its beginnings in the faith of its machinery suppliers, who accepted company

stock for the value of their machinery when Northern investors pulled out before the mill was

completed.The company again relied on faith to remain solvent in 1913. It asked company

stockholders to subscribe $250,000 and issued a large block of preferred stock, which later was

redeemed. This was the only time that additional stock had to be issued.Avondale shook off its

financial woes and, like Walton Monroe, prospered. Between 1917 and 1921, the company built six

mills in the South, and increased the number to 10 by 1933.The year 1921 saw the advent of

Avondales first annual inspection tour, a forerunner to Avondales current Zero Defects (ZD) program

and facility-auditing program. ZD recognizes associate dedication and encourages communication

between employer and associate for the improvement of the company.The annual inspection tour was,

at first, a small, businessmen-only event that was arranged to encourage associates to take pride

in their work and in the plant as a whole.In typical Avondale style, the tours turned into

something far grander and more meaningful, with community leaders, customers and friends of the

company tagging along for the inspections, which were followed by full-scale banquets at the mill.

Associates came to take such pride in their work that they began to decorate their workstations

with flowers from their own gardens. On The Home Front

The onslaught of World War II forced the textile industry into the war effort. Avondale,

Graniteville and Walton Monroe jumped into the cause, continuing the similar pace they had kept up

during the first part of the century.Items made for the war effort included: woolen blankets for

the Army; knitted yarns for the manufacture of Army and Navy undershirts, underwear and socks;

camouflage nets; herringbone twills used in fatigue uniforms for both training and actual combat;

tent fabrics; sanforized drills for trouser pocketings and waist bands; wide and narrow tickings

and linings for military mattresses and mattress covers; and seersuckers for service hospitals

throughout the nation.Avondale was twice awarded the Army-Navy E Flag for outstanding production of

quality products delivered on a timely basis during the war effort. A Time Of ProsperityThe

last half of the century saw the three companies grow with the post-war economic boom.High-profile

advertising campaigns during this time gave Avondale a greater presence within the textile

industry, and showed both its customers and its associates that it was at the forefront of the

industry.Avondales most expansive campaign came in 1947 in the Saturday Evening Post. A monthly

series of full-page advertisements depicted Avondale associates and their families in paintings by

Douglass Crockwell.

The Companion Colors campaign came three years later. It was another series of nationwide

advertisements that ran in such publications as Ladies Home Journal, Vogue, McCalls and Good

Housekeeping, among others.Around the same time, Avondale, Graniteville and Walton Monroe made

improvements to almost all of their plants. Investments were made in technological advancements,

such as new opening equipment, combers, magic eye doors, lighting systems and continuous overhead

cleaning devices. Central air conditioning, however, didnt come until 1963, when the Walton plant

was among the first to receive this luxury.The trios ability to weather the storms of war and

unstable economic times enabled all three to expand their operations, as well as upgrade them. More

than 17 plants were either bought or built by Avondale, Graniteville and Walton Monroe between 1961

and 1994.Running on what seemed like parallel currents in the same river, the three companies

flowed closer and closer together as the 20th century came to a close.Walton and Monroe officially

merged in 1968 to become Walton Monroe Mills, Inc. In 1975, Avondale Mills acquired Cowikee Mills,

an Alabama company founded in 1888 and, since 1913, also owned by the Comer family.The currents

rushed even closer together in 1986, with the purchase of Avondale by Walton Monroe Mills, Inc. The

two companies operated separately, but were managed by the same Board of Directors.In 1993, the two

finally merged, taking the name Avondale Incorporated. Avondale Mills, Inc., now operates as a

wholly owned subsidiary of Avondale Incorporated.Three years later, Avondale acquired the textile

assets of the Graniteville Company, adding five more plants to the Avondale family. Just The

BeginningThe textile industry has seen many companies washed away by the overwhelming forces of

economic instability and change in product demand. It is rare to see a manufacturing operation that

has weathered so many storms still standing strong after more than a century and a half. But, it is

this steadfastness in inclement times that makes Avondale stand out. It is because of the companys

long history of unity and commitment that its future remains promising.Our rich history has

culminated in a corporate culture that demands excellence from each of our associates, said G.

Stephen Felker. This culture permeates and thus vivifies our entire enterprise.The story of

Avondales road to prosperity may seem a little complicated, but mergers and acquisitions by

companies with similar investors, work ethics, dedication to product advancements and concerns

about employee welfare helped the individual companies become the success that Avondale is today.

June 2002

For The Record

For The Record:Ramtex uses Trutzschler 803 and 903 cards to prepare sliver at about 120 pounds per

hour for its 70 Rieter SB D10 and RSB D30 drawframes. The company weaves more than 900,000 yards of

fabric per week, 130,000 of which are produced using 14 Sulzer multiphase machines

(See Ramtex, TW, May 2002).

June 2002

Easy-Care Cotton Inventor Receives Achievement Award

Easy-Care Cotton InventorReceives Achievement AwardDr. Ruth Rogan Benerito, inventor of easy-care cotton, has received the eighth annual Lemelson-MIT Lifetime Achievement Award for invention and innovation. The $500,000 award was presented during a special ceremony at the San Francisco Museum of Art by the Lemelson-MIT Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, Mass.Dr. Benerito, who worked for 33 years at the Southern Regional Research Center of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, is credited with saving the cotton industry in the years following World War II, when fabrics made from man-made fibers were gaining popularity over cotton fabrics among American consumers. Her theory of crosslinking cellulose chains in cotton to provide wrinkle, stain and flame resistance received the first of 55 U.S. patents for processes used in cotton production. Dr. Benerito also created an environmentally safe process for the pretreatment of cotton, replacing mercerization using sodium hydroxide with radiofrequency cold plasma cleaning. The process was later adopted by the Japanese textile industry.June 2002

Stork Introduces Sapphire Digital Ink-Jet Printer

Stork Introduces SapphireDigital Ink-Jet PrinterThe Netherlands-based Stork Digital Imaging has introduced the Sapphire digital ink-jet printer. The printer uses piezo drop-on-demand ink-jet technology and can print on a variety of natural and man-made substrates, including silk and polyamide.Print speeds of up to 32 square meters per hour are possible, and the printer is suitable for short runs and roll-to-roll printing. In addition, the PrinterServer software guarantees quality reproduction and high color consistency, according to the company.Stork also offers specially pretreated textiles or, for customers wishing to use their own substrates, the necessary fabric pretreatment chemicals or Storks pretreatment license.June 2002