T

he implications of increased economic relations between the United States and China have

been the topic of debate for some time – particularly as China acceded to the World Trade

Organization (WTO). Often, the discussion devolves into a trade theory argument. In a search for

clarity, following are direct excerpts from The US-China Economic and Security Review Commission’s

Report to Congress, published in June 2004. The 290-page report details growing concerns reached

through a broad and bipartisan consensus.

The report summary states: “Based on our analyses to date, as documented in detail in our

Report, the Commission believes that a number of the current trends in US-China relations have

negative implications for our long-term economic and national security interests, and therefore

that US policies in these areas are in need of urgent attention and course corrections.”

Overview

The overvaluation of the dollar against the world’s currencies has been a major contributing

factor in the worsening of the US trade deficit over the last several years. Of particular concern

is the undervaluation of the yuan [currency of China] against the dollar. China pegs its currency

to the dollar, and the yuan has traded at 8.28 per dollar since 1998.

During this period, China has experienced massive export sector productivity growth driven

by FDI [Foreign Direct Investment]. This situation has enormously strengthened China’s competitive

advantage, rendering the yuan undervalued. In a free market, China’s productivity growth, trade

surplus and inflows of FDI would have caused significant exchange rate appreciation. However, China

systematically intervenes in the currency market to prevent this from happening, thereby

maintaining an important competitive advantage for Chinese exports.

Impact Of China’s

Exchange Rate Policies On US Trade

International trade is dominated by manufacturing trade, and overvaluation of the dollar has

significantly reduced the international competitiveness of US manufacturing industry. This lack of

competitiveness is reflected in the growing US trade deficit, which has negatively impacted

manufacturing output and employment. The negative effects of the overvalued dollar on manufacturing

operate through several channels.First, overvaluation makes exports relatively more expensive,

reducing foreign country demand for US manufactured goods.

Second, overvaluation makes imports cheaper, inducing a substitution in spending away from

domestically produced manufactured goods to foreign-produced goods.

Third, overvaluation reduces the profitability of US manufacturing firms by making foreign

goods cheaper, and this reduces firms’ incentive to invest in new production capacity.

Fourth, by making US-based production relatively more expensive, an overvalued dollar gives

US companies an incentive to shift production offshore and to build new production facilities

offshore.

These negative effects on the trade deficit and manufacturing in turn adversely impact

overall US economic growth. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the US goods trade

deficit lowered GDP growth by 0.09 percent in 2001, 0.71 percent in 2002, and 0.42 percent in 2003.

The trade deficit therefore deepened the recession and is hampering the recovery.

The critical economic significance of exchange rates was summarized in the testimony before

the Commission by Franklin J. Vargo: ”Only 11 percent of the cost of a US manufactured good is

labor. If a product gets a 20- or 40-percent price advantage because of a currency, that is a much

more significant factor.”

The reason is that currency misalignments work on the entire cost base, so that an

overvalued currency raises the entire cost structure.

The Overvalued

Dollar And Undervalued Yuan

There is widespread agreement the dollar has been overvalued against the currencies of the

world’s major trading countries. With regard to China, the Commission heard testimony that the yuan

is undervalued by between 15 and 40 percent. Based on this testimony and other economic evidence,

the Commission believes that:

• the yuan needs to be revalued substantially upward against the dollar;

• as part of this revaluation, the yuan should be pegged against a

trade-weighted basket of currencies to avoid excessive fluctuation against the currency of any

single country;

• China should refrain from adopting a floating exchange rate at this

time, as its banking system and financial markets are not yet prepared for such an arrangement; and

• China should take active steps to reform its banking system and

financial markets to prepare them for an eventual floating exchange rate.

Case For Revaluing The Yuan

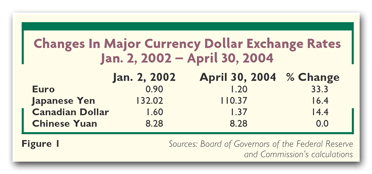

The dollar has now entered a period of correction against the currencies of other

industrialized countries. As shown in [Figure 1], since January 2, 2002, it has fallen 33.3 percent

against the euro, 16.4 percent against the yen, and 14.4 percent against the Canadian dollar. In

addition, it has also fallen significantly against other currencies such as the pound sterling and

the Australian dollar. However, there has been no adjustment against the Chinese yuan, which is

fixed through official intervention. Additionally, there has been little in the way of correction

against the Taiwanese, South Korean, and Singaporean currencies, all of which countries run large

trade surpluses with the United States. This lack of adjustment has occurred despite the fact that

there is compelling evidence that the yuan is undervalued. China now constitutes the single largest

contributor to the US trade deficit, and economic fundamentals support the claim that the yuan is

undervalued.

China’s economy has been characterized by a trade surplus (external imbalance) and by rapid

economic growth with incipient inflation (internal imbalance). A currency revaluation will help

restore both trade balance and domestic economic balance by reducing exports and reducing demand

for domestically produced goods.

Conversely, the US economy has a large trade deficit (external imbalance) and excess

capacity and unemployment (domestic imbalance). Dollar devaluation will help restore both external

and internal balance by increasing exports and demand for US-produced goods.A revaluation of the

yuan is also needed for global economic equilibrium. As noted above, the United States has

significant trade deficits with other East Asian economies, including Taiwan and South Korea. These

economies are apprehensive about revaluing their currencies for fear that they will lose

competitiveness relative to China.

A revaluation of the yuan would likely free this logjam, allowing these economies to revalue

too, thereby smoothing and accelerating the process of dollar adjustment.

Additionally, failure to revalue China’s currency while currencies of other major trading

partners appreciate promises to cause economic disruption. This is because other economies – such

as Japan and the euro area – are implicitly being forced to take on a larger burden of adjustment

to correct the US trade deficit, while the country with the largest surplus (China) undertakes no

adjustment.

Arguments Against Revaluing The Yuan

Some argue the yuan does not need to be revalued. The Commission rejects this position.

One argument is that revaluing the yuan could lead to a financial crisis in the Chinese

banking system that ends up perversely generating a lower value of the yuan. The claim is that

opening China’s capital account and floating the yuan risks a massive exodus of Chinese savings

that could trigger a domestic financial crisis and yuan depreciation. Thus, paradoxically, capital

account liberalization and yuan floating could actually cause depreciation rather than

appreciation.

However, this argument confuses revaluation of China’s exchange rate with a shift to a

floating exchange rate. The Commission does not recommend floating the yuan at this time. Instead,

China should significantly revalue the yuan upward while maintaining capital controls and a fixed

exchange rate over the near term. This would address the underlying balance of payments

disequilibrium problem while avoiding financial crisis.

China has begun to recognize its problem of domestic financial fragility, but must now

accelerate the process of remedying it. The fact that capital account opening could trigger a

massive outflow of Chinese bank deposits reveals the inhospitable climate of Chinese financial

markets for domestic wealth owners. China must therefore move to make its financial assets more

attractive. The threat of domestic capital flight is not going to disappear. Indeed, it stands to

grow in magnitude as Chinese household financial wealth grows with development and households in

turn seek to diversify their portfolios internationally.

The bottom line is that China’s domestic financial fragility does not justify an undervalued

exchange rate that exports deflationary pressures and destroys US manufacturing jobs.

A second argument is there is no need to revalue, since market forces will force a

revaluation despite the Chinese government’s exchange rate intervention.

This argument is based on the discredited economic doctrine of monetarism. The claim is that

China’s persistent trade surplus forces its central bank to sell yuan and buy dollars to prevent

appreciation and that this expands the money supply, which will in turn cause inflation that drives

up Chinese prices. As a result, China will gradually become less competitive, while US

manufacturing companies will become more competitive.

The above monetarist argument is flawed. First, even if the mechanism worked, there are long

and unpredictable lags between expansion of the money supply and higher prices. In the meantime,

American manufacturing firms may be compelled to close down, with consequent loss of jobs.

Second, Chinese monetary authorities can take measures to mitigate the effect of a rising

money supply on prices. These include raising reserve requirements in the banking system and

sterilizing the monetary expansion by selling bonds and thereby withdrawing money from circulation.

A third argument is that the China trade deficit is unrelated to the exchange rate and is

the result of a shortage of US saving – principally the result of the large US government budget

deficit.

The argument is the US economy is consuming in excess of what it can produce and has to

import the balance. The Commission believes the United States must address its chronic budget

deficits, but it rejects the notion that this obviates the need for China to address its currency

undervaluation.

Contrary to the claims of the saving shortage hypothesis, the US economy currently has

severe excess manufacturing capacity and is capable of producing significantly increased

manufacturing output. A shortage of national savings is not the problem. The real problem is that

the misaligned exchange rate results in US goods being too expensive relative to foreign goods.

This drives down demand for US-produced output, and, over a more extended time period, contributes

to the elimination of US manufacturing capacity and the creation of a structural trade deficit.

Plant closures and the loss of well-paying jobs in turn undermine the tax base and contribute to

state and local fiscal problems.

A fourth argument is that though the United States has a large trade deficit with China,

China’s overall trade surplus with the rest of the world has been much smaller, and in the first

quarter of 2004 it registered a small deficit. Consequently, China’s currency may not be

undervalued.

Again, the Commission rejects this argument. [Figure 2] shows the United States has a trade

deficit with every region of the world, and the deficit with China is especially large. This

pattern points to a need for a generalized realignment of the dollar, and China should revalue its

currency as part of that realignment.

Second, for the last several years, China has run a global trade surplus. Moreover, the fact

that China has run a surplus even as it grew at 9 percent per annum is compelling evidence of

undervaluation. Any other country that grew at that rate would have quickly run up a huge trade

deficit. The small move into deficit in the first quarter of 2004 reflects continuing breakneck

growth and rising commodity prices, particularly in oil. That China still essentially has balanced

trade under these conditions is testimony to how undervalued the yuan is.

Finally, China is also running a capital account surplus generated by the flood of FDI into

China. This means China has an enormous basic balance surplus, defined as the combined surplus on

current and capital accounts. Thus, in 2003, China had a current account surplus of $45.9 billion

and a capital account surplus of $52.7 billion, making for a basic balance of $98.6 billion. This

put significant upward pressure on the exchange rate, but purchases of $116.8 billion of foreign

exchange by China’s central bank prevented the exchange rate from appreciating.

Editor’s Note: The US-China Economic and Security Review Commission’s Report to Congress is

available in full at

www.uscc.gov.

Textile World wishes to thank Associate Director Kathleen J. Michels for

permission to excerpt.

December 2004