Will Productivity Save U.S. Textiles

Shedding light on the battle between U.S. manufacturing efficiency and textile importsA

recent article in the

Wall Street Journal (WSJ), The Welch Legacy: Creative Destruction, pays obeisance to the

20-year reign of Jack Welch at General Electric (GE). The author posits that Mr. Welchs true legacy

is changing the GE culture from being operationally sensitive to being capital-sensitive through an

almost religious dedication to the gales of creative destruction described in the 1930s by the

Austrian-American economist, Joseph Schumpeter.Welch and Schumpeter argue that a company

continuously must reinvent itself to create a corporate atmosphere in which the internal rate of

change matches or exceeds the rate of change in capital markets. This external pressure is more

important than constant application of assets to improve efficiency against some arbitrary

yardstick, and it offers growth industries opportunities to share in the distribution of wealth

assets.Welch recognized that destroying ones businesses or knowing when to let go of them and move

in another direction is a far surer way to protect what youve built, regardless of how grand,

Richard Foster wrote in the Journal. Corporate life is driven by the contradictions of survival; it

cannot succeed without excellent operations, but it will fail if it focuses primarily on operations

(Foster,

WSJ). The corporation is afflicted with the survivors curse, operational efficiency at

virtually any cost, including exclusion from market-driven efficiencies of capital allocation.

Control processes, designed to ensure the continuity of operational efficiencies, deaden

[corporations] to the need for change (Foster,

WSJ).Capital markets are built on assumptions of discontinuity; their focus is on creation

and destruction (Foster,

WSJ) of providers of products and services desired by the consumer. The market allocates

capital to those industries and companies that offer returns exceeding the costs of capital, and

corporations are rewarded when they provide internal returns exceeding the returns on capital

available in the external market. The corporate challenge is in managing to achieve rates of change

the same as or larger than the rates of return on capital external markets.Surveying the

textile/apparel complex against a Schumpeter/Welch backdrop suggests that while many resources have

been spent performing existing activities in an efficient manner, few resources are expended on

efficacy or effectiveness, the throwing out of old habits and replacing them with

new. Industry ProductivityTo understand this efficiency/effectiveness dichotomy, several years

have been spent trying to build a Productivity Index able to measure the textile industrys ability

to improve labor efficiencies to stave off continued import incursions. The starting hypothesis was

that an inverse relationship exists between the volume of imports and the efficiency with which the

domestic industry converts raw materials into finished products. To this end, Bureau of Labor

Statistics data were used to calculate the amount of labor dollars involved in converting total

domestic fiber consumption (domestic production plus imports of fiber) into textile mill products

(SIC 22) and divide the total dollar amount by total fiber consumed as reported by the Fiber

Economics Bureau.The resulting product indicates the number of labor dollars required to convert

one pound of fiber into a finished textile mill product. As this indicator shrinks, it should

herald a victory of mill efficiency over imports. The challenge is to find the level of efficiency

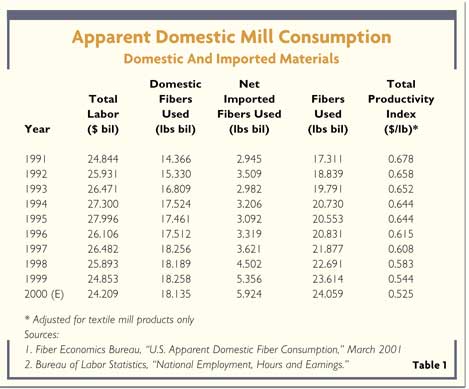

that holds imports at bay. This hypothesis led to the relationships detailed in Table 1.It is

accepted as gospel that the U.S. textile and apparel complex is drowning in imports from all over

the world, particularly from Southeast Asia. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has

performed as expected in diverting imports from Asia to Mexico, but the basic fact of a deluge of

imports remains a major issue. To be sure, the amount of apparel imports has increased

dramatically, followed closely by fibers and fabrics from corners of the world anxious to advance

their standards of living with cheap labor. Unfortunately, there is little the industry, or even

the broader U.S. economy, can do to change international wages as countries exporting to the United

States use apparel to accumulate hard currencies and trade surpluses on the backs of labor. Is

efficiency the way to compete, or should the creative destruction strategies of Welch and

Schumpeter be explored

Labor CostsSeveral relationships, which can serve to open the creative destruction

dialog, leap out of the Productivity Index database. First, total labor costs in the U. S.

textile/apparel complex have not risen significantly in the past 10 years. Total dollars did rise

in response to mid-1990s economic exuberance, but they settled back to historic levels late in the

decade. As an aside, the labor statistics are not corrected for inflation, so the industrys real

wage costs, in fact, have fallen in the period.Simultaneously, U.S. fiber and fabric manufacturers

have performed yeoman service in decreasing the unit cost of labor to produce a pound of fiber and

convert it into fabric. The U.S. Productivity Index dropped 22+ percent, from $0.678 per pound of

conversion in 1991 to $0.525 per pound estimated for 2000, a compounded average of 2.88 percent per

year. It must be noted that some of this improvement results from changes in product mix measured.

For example, the amount of woven materials included in the index has decreased over time, while the

amount of nonwoven materials has increased dramatically.Conversely, the amount of home fashions and

industrial materials has grown, while the quantity of fabrics produced for apparel has decreased

during the period. As a general rule, home fashions and industrial materials are run in smaller lot

quantities than apparel, often have more complex patterns and structures than those designated for

apparel, and, resultantly, require higher amounts of labor than traditional large-quantity apparel

materials.Fiber consumption in textile mill products for the non-carpet fashions market area have

risen 19 percent since 1991. This rate has slowed in recent years in response to market saturation

and a slowing U.S. economy. Similarly, fiber consumption in the production of industrial textile

mill products has risen 36 percent, but it also is slowing in response to the same pressures that

are slowing home fashions.Unfortunately, there is precious little data available to adjust the

index for product mix; it is assumed that these variables tend to offset, and comment is based on

the index in its raw form. In any case, it is absolute that the labor cost to convert one pound of

materials into textile mill products has decreased significantly in the past 10 years.It should be

noted that, while the Productivity Index shows recent mill efficiency improvements, the index

cannot continue to fall indefinitely. At some point, the investment needed to decrease labor costs

an additional unit will exceed the savings obtained by eliminating that unit. Continued improvement

will fall victim to the limits of decreasing rates of increase. Rising Domestic Fiber

UseSecondly, surprisingly, the use of domestic fibers in domestic mills continues to rise. Current

readings in some of the trade press could make a reader believe that everything textile was

imported. Quite the contrary, domestic mill consumption of domestically produced fibers has risen

26+ percent, from over 14 billion pounds to slightly over 18 billion, a 2.62-percent annual

compounded rate. True, net imports virtually doubled in the same period, from 2.9 billion pounds to

over 5.9 billion estimated for 2000, but some of this increase is offset by domestic manufacturers

changing product mix offerings and producing the new items more efficiently.Imports have taken two

paths to the current level. From 1991 through 1996, imports grew at an annual rate of 2.4 percent,

a level probably appearing sufficiently small to be manageable. From 1996 through 2000 however, the

rate skyrocketed to a 15.6-percent increase in annual rates. It appears that U.S. manufacturers

used efficiency programs to effectively hold imports to modest growth, until the Asian currency flu

hit in 1997 and the Tiger Nations attempted to export their way out of crisis. It appears that no

manner of efficiency improvements would deflect the political/economic decisions of exporting

nations to avoid a countrys failure by exporting, which keeps people employed and enables the

accumulation of hard currencies needed in world trade. A Case History

At the recent Springs Industries annual meeting, Chairman and CEO Crandall Bowles cited some

interesting productivity statistics. In 1966, the year Springs went public, the company generated

approximately $266 million in sales from 19 plants with 17,000 employees. This year, as the company

reverts to private ownership, revenue nears $2.3 billion from 41 plants using the same number of

employees. Using a traditional industry measure, 1966 sales per employee were $15,647; in 2001 the

measure reached $135,294, a 765-percent increase. Adjusting this calculation for inflation still

yields an impressive statistic.Since, in 2001, $5.48 buys one 1966 dollar (U.S. Bureau of Labor,

Statistics Inflation Calculator) the adjusted Springs efficiency still tops 57 percent, well ahead

of the change predicted by the Productivity Index. This certainly points to Springs dropping less

profitable lines and adopting/developing products with better returns. ConclusionsThe

Productivity Index shows clearly what the textile mill products industry has been able to

accomplish in reducing labor costs to improve world competitiveness. Unfortunately, it is a logical

calculation, and it is somewhat insulated from the economic/political pressures surrounding import

strategies. As such, it is not yet a valuable test of the textile industrys ability to improve

through efficiency, and it does nothing to lead us to efficacy.However, one major conclusion of the

Productivity Index appears to be a very strong suggestion that mill closings and labor losses are

as much a result of improving mill efficiencies as they are of imported products, particularly

apparel. If this is the case, it may be that continuing to improve mill efficiency is a

self-defeating goal. True, if imports did not exist, more mills would be open and more people would

be employed. Unfortunately, this is an unrealistic view of the world. Imports soon will accelerate,

prompted by full implementation of the World Trade Organization, and the situation will only get

worse. Textile mill product producers have continued to lose market share and business by

continuing to focus on efficiency to save them.How long will it take before the industry accepts

the admonitions of Welch and Schumpeter to change the business and weed out the old and invest in

the new Be honest in asking, What business should we be in What business will generate internal

rates of change consistent with the rates of change in capital markets Just because you produce a

certain product mix does not mean that mix will or can carry you in the future.Investment is

difficult without significant cash flows to support new technologies. The industry appears to be

nearing extremes from which no amount of investment will rescue it. Its expensive and risky to

invest, but it is fatal not to invest. A good industry is facing death on the back of efficiency if

it does not escape to the safety of the arms of efficacy.

Editors note: John E. Luke is owner of Five Twenty Six Associates Inc., Bryn Mawr, Pa., a

consulting firm specializing in strategic marketing and operations facing textile fiber and fabric

manufacturers. He is also a professor of textile marketing at Philadelphia University,

Philadelphia.

November 2001