It’s been another tolerably good year for U.S. mills and apparel manufacturers. And barring the

unforeseen, there’s little to suggest otherwise, not only for the new year but also well into the

second half of the decade.

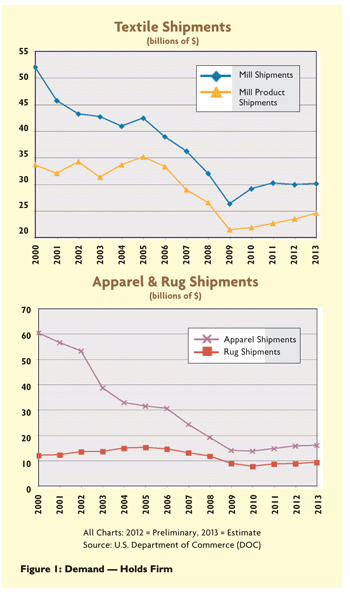

Domestic mill shipments, for example, should approach $54 billion to $55 billion in 2013 —

the fourth consecutive year that totals have held steady or inched ahead. And the same is likely

for apparel, for which the new year’s shipment total will approach $16 billion — more than a

double-digit percentage gain over 2010, when the industry hit its recession low.

Do the math, and all this adds up to a $70 billion to $71 billion textile and apparel

industry — not bad for a sector that many analysts were writing off as a lost cause as recently as

four to five years ago.

And the picture is even brighter when it comes to industry profits. Indeed, anticipated

after-tax earnings gains for 2013 are quite impressive — nearly double last year’s for textile

mills.

Nor are these projections based on just a lot of wishful thinking. Quite the contrary —

Textile World

‘s new numbers are solidly buttressed by an imposing list of positive signs, including:

- An improving macroeconomic outlook: For one,

TW

feels that by avoiding a fall off the fiscal cliff, gross domestic product (GDP) — the

economy’s all-inclusive measure of health — will advance another 2 to 2.5 percent, and probably

approach the 3-percent rate by the following year. Moreover, once the 3-percent level is reached,

there could be some meaningful progress in bringing down the still-uncomfortably-high domestic

jobless rate. - Stronger consumer financing positions: Household debt payments as a share of after-tax income

are at their lowest point in 20 years. Access to credit is also improving, and home refinancings

have freed up a lot of additional cash for apparel and other consumer goods. - Substantial housing recovery: The huge construction decline stemming from the 2008-09 mortgage

collapse is beginning to reverse itself — with new starts up significantly over the past few

months. This is not an unimportant shift, as construction accounts for a sizable portion of textile

sales as well as U.S. employment and GDP. - Leveling imports: This past year’s flat pattern of incoming textile and apparel shipments,

following the previous year’s small decline, would seem to confirm that earlier big U.S.-foreign

price differentials may be starting to narrow a bit. - Improved industry strategies and planning: These would have to include increased management

emphasis in such areas as sourcing, inventory control, use of more flexible and efficient machinery

and equipment, new and upgraded consumer products, more ecologically friendly offerings, and more

Made-in-USA labels. More on all these production and marketing strategies below.

To be sure, there’s always a chance that an unexpected factor — a war, a euro crisis or

continuing Washington political squabbles — could dim the above scenario. On the latter score,

however,

TW

feels that chances of any major economic shock are relatively small. Nevertheless, these

uncertainties should serve as a reminder that close monitoring and periodic reviews should continue

to be the order of the day.

With all the above in mind, here’s a more detailed look at what

TW

sees ahead, both for the new year and beyond:

Demand Holds Firm

As noted above, dollar shipments of textiles and apparel will on the whole match or even

inch a bit above last year’s levels. But there could be some differences among the industries’

various subsectors. Mills making basic products like fibers and fabrics, for example, aren’t

expected to do much more than match their 2012 performances.

On the other hand, mills specializing in more highly fabricated products like rugs, home

furnishings and industrial products should rack up some modest gains. This is most likely in the

carpet area, as an improving construction market beefs up demand. Given this prod, rug and carpet

shipments could rise about 5 percent or so in 2013 — reaching their highest level since 2008.

And there are indications this recovery could continue for at least another few years. Based

on one research firm’s projection, floor coverings can expect close to an 8-percent annual rate of

growth in square-foot terms over the 2010-15 period, with tufted carpet and rug products —

especially broadlooms — sparking the advance.

Meantime, another solid year of auto sales will help mills making automotive interior

fabrics. This is an important market, too. According to one recent estimate, well over 20,000 tons

of textiles are needed for upholstery, headliners and door panels. Moreover, this doesn’t include

significant amounts going into such areas as carpets, floor mats, tire cord, molded parts, seat

belts and even airbags.

Add in other industry usages, and overall U.S. shipments of fabricated mill products could

rise by upwards of 4 percent — making for a second straight year of solid growth.

The outlook for apparel also doesn’t seem to be all that bad. The fact that recent holiday

sales managed to post a small gain in the face of today’s uncertainties suggests consumers are

becoming more willing to spend on new clothing after several years of what can only be described as

penny-pinching on wardrobes.

Another positive factor here: Men are becoming more clothes-conscious, with 2012 sales of

those items up by 2 to 3 percent. And, in the case of men’s outerwear, the increase has been near 6

percent. This is a lot more substantial than the only fractional gains reported in womenswear —

and, if nothing else, suggests an added plus for overall U.S. apparel purchases.

Still another upbeat sign for clothing manufacturers is the fact that imports of those

products have been leveling off. Indeed, incoming shipments of clothing actually fell some 2

percent over this past year. Couple this with the just-discussed better consumer buying outlook,

and there’s a better-than-even chance that 2013 shipments of domestic apparel could again show a

small gain.

Import Penetration Slows

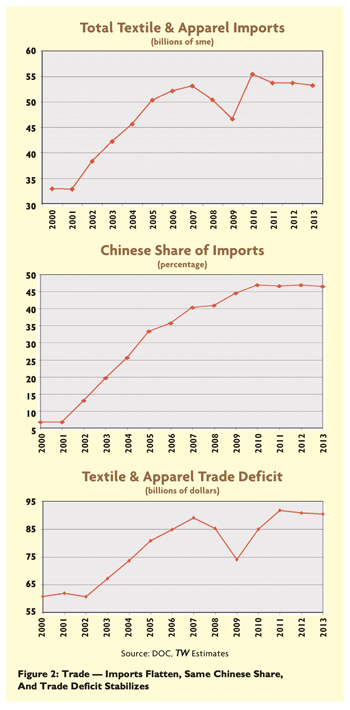

Several factors could be contributing to the above-noted apparel import slowdown — which is

also having a braking effect on incoming shipments of textiles. Probably one of the most important

is the fact that foreign producers have already picked most of the low-hanging fruit. Or put

another way, there are now few vulnerable markets left to capture.

But rising overseas costs could also be playing a major role — especially when it comes to

China, which at last report was supplying a hefty 46- to 47-percent of all U.S. textile and apparel

imports.

More important, Chinese production costs are likely to continue rising over the next few

years. A recent survey by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) involving more than 100 large U.S.

manufacturers — including some textile and apparel firms — pretty much tells the story. One key

projection: more sharp price increases — enough to erode Beijing’s position as the world’s low-cost

provider.

The research outfit, in detailing the changing Chinese competitive position, also notes the

following:

- More than one-third of surveyed companies now are either planning or actively considering the

reshoring of some of their China production back to the United States. - Beijing sourcing is a lot more costly than simple per-hour labor cost comparisons would

seem to indicate — primarily because of much higher U.S. productivity. - There are other intangible advantages for reshoring — including product quality, proximity of

customers and ease of conducting business.

Still another key BCG prediction is that by the current decade’s end, the narrowing

U.S.-Chinese price gap should both create two million to three million new American jobs and reduce

the U.S. jobless rate by some one to two percentage points.

Research by The Hackett Group, another consulting firm, pretty much backs up BCG’s

conclusions. As The Hackett Group puts it, “the tide has begun to turn on the flow of manufacturing

jobs from the U.S. to China and other low-cost countries.

“Some companies are already reshoring a portion of their manufacturing capacity and this

trend is expected to reach a crucial tipping point over the next 2-3 years as the total landed cost

gap between the two nations continues to shrink, driven in part by rising wage inflation in China

and continued productivity improvements in the U.S.”

In any case, reshoring is expected to become more viable with each passing year as the total

landed cost gap for imports shrinks. The Hackett Group finds that the cost gap between the United

States and China has shrunk by nearly 50 percent over the past eight years. It’s expected to stand

at just 16 percent this year — with the trend driven by rising labor costs in China as well as

rising fuel and shipping costs.

But despite all this, it would be unrealistic to expect any big return to domestic textile

and apparel sourcing. For one, even if there is some decline in sourcing from China, it would

probably be replaced by a substantial shifting over to other low-cost foreign suppliers. Indeed, a

fair amount of this switching is already occurring.

Secondly, China is now taking some corrective steps to counter any wholesale loss of its

U.S. customer base. In many instances, for example, the Chinese are stepping up their purchases of

more automated, labor-saving equipment. Equally important, the rise in the value of Beijing’s

currency, the yuan — something which tends to boost the price of Chinese products — has stalled,

with little indication of any change over the next few years.

Bottom line:

TW

‘s import projections for 2013 point to a basically flat pattern — with only an outside

chance of some fractional decline. On a brighter note, however, that should be enough to leave the

incoming total some 4 percent under the 2010 all-time high.

There’s also a modicum of good news on the export side of the trade equation — with outgoing

textile and apparel shipments moving up in 2012 for the third consecutive year — enough to bring

totals some 36 percent above the 2009 low point. And another modest increase seems likely for 2013.

Couple this with the basically flat import level anticipated for the new year, and it should make

for the second straight year of small declines in the U.S. textile/apparel trade deficit.

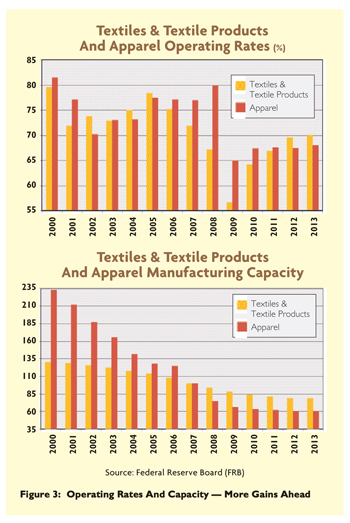

Changing Production Potential

Meantime, the relatively improved demand outlook referred to above is helping to slow down

the past few years’ slide in textile and apparel production capacity. Indeed, domestic mill

production potential at last report was slipping at only a 2-percent annual rate. That’s well under

the near-5-percent pace of the recent 2003-10 period.

Changes are even more dramatic in the clothing sector, where the capacity decline has slowed

down to only about 1 percent a year. That’s far under the near-6-percent annual tumble noted in the

early 2000s.

Credit two factors for this flattening out in domestic production capacity. One, as just

noted, is the encouragement to invest, fostered by a somewhat brighter demand outlook. But an

equally important contributor has been growing competitive pressures — pressures necessitating more

investment in new, more efficient capacity or the facing of additional losses to foreign suppliers.

How much, then, are U.S. domestic firms spending? Preliminary evidence suggests a pretty

impressive sum — probably upwards of $1 billion a year. That’s pretty much what they were shelling

out a decade ago, when the market potential was much larger.

Nevertheless, despite the magnitude of these outlays, there’s still no surefire guarantee

that this strategy can recapture any sizable part of domestic firms’ lost markets. That’s primarily

because foreign suppliers, facing their own cost and competitive pressures, are also stepping up

their capital spending.

A recent study by research outfit Global Industry Analysts Inc. would seem to confirm this

worldwide investment uptick. That company sees the global market for textile machinery growing to a

hefty $23 billion by 2017. It attributes all this spending to a shift from conventional machinery

requiring the availability of cheap labor to more sophisticated equipment that can produce better

and cheaper products. In short, producers around the world are increasingly seeking automation

solutions in their efforts to hold onto or even expand their markets.

One thing for sure, textile and apparel operations are going to look a lot different in just

a matter of a few years — with production and distribution not only becoming more efficient, but

also a lot more flexible, allowing for both smaller and faster deliveries.

This latter development, in turn, could further facilitate the ongoing trend toward

inventory retrenchment. That’s something that would also bolster bottom-line performance inasmuch

as industry stocks in factories and warehouses constitute one of the industry’s major cost drains.

Still another point to make on the changing face of capacity: This ongoing capital

investment should also provide the industry with a better green footprint. Clearly, all the current

new equipment and that expected to come onstream in the near future will reduce air and water

pollution. And, as an added ecological plus, this modernization drive includes the opening of a

spate of new recycling facilities to convert textile waste into new textile uses and resins.

Finally, before leaving the subject of investment, it’s important to keep in mind that all

the new spending will keep factory utilization rates low — as the opening of new, modern plants

offsets the retirement of older ones. This, in turn, means that operating rates for both textiles

and apparel should remain stuck in the low 70-percent range.

Unfortunately, those rates are well under preferred rates. In fact, they’re so much under

that they would seem to guarantee a continuation of the sharp price competition that has

characterized all segments of the U.S. industry for more than a decade now.

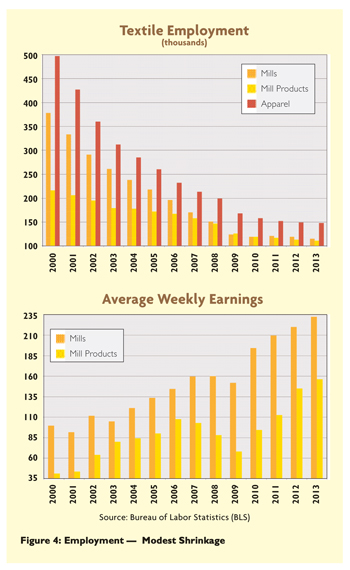

Labor Costs And Productivity

It’s also worth noting that anticipated increases in industry efficiency, when combined with

only minor hourly pay boosts, should help keep unit labor costs under control. In fact, that’s been

the case for several years now, and there’s little to indicate any near-term change.

A few key industry statistics tell the story here. This past year, textile mill pay hikes

averaged out at only 2 to 3 percent. But productivity — measured by comparing the number of workers

to the amount of product turned out — has been rising by a slightly higher 3-percent-plus rate. The

implication is clear: Mill labor costs to produce one unit of output have actually been edging a

bit lower.

Moreover, as far as productivity is concerned, the 3-percent-plus annual rate of increases

in efficiency seems all but certain to continue. And, make no mistake about it, that’s a pretty

impressive number. Indeed, it’s a full percentage point above the productivity gains that

government forecasters see for all U.S. manufacturing over the same time span. In short, domestic

mills could well be outperforming the overall economy as far as efficiency gains are concerned.

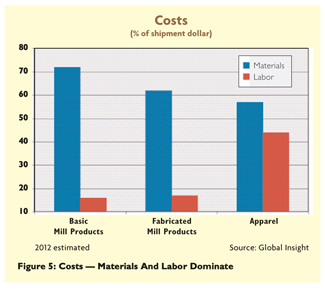

This is especially important for U.S. mills, where labor accounts for a significant share of

the typical textile sales dollar. Based on figures supplied to

TW

by economic consulting firm Global Insight, for example, labor’s share of the mill sales

dollar comes close to 16 to 17 percent.

The same pattern is apparent for apparel. Indeed, labor is an even more important factor

here, draining upwards of 40 percent of the typical apparel manufacturer’s sales dollar.

But holding these costs down through efficiency gains can also have a negative impact —

namely, a smaller industry workforce. In the textile sector, for instance, squeezed by productivity

gains, overall employment should drop from 232,000 in 2012 to near 209,000 by 2015. The only

consolation is that the annual decline comes to only about 3 percent — far lower than the tumbles

of earlier years.

The picture is much the same for apparel, where similar job declines are expected — bringing

that workforce down by another 11,000 over the three-year period ending 2015.

All told, this means the United States’ total textile and apparel job number will drop to

near 350,000 by 2015. Go out another five years to 2020, and the overall number drops further, to

285,000 workers.

But that’s still a relatively significant number. According to the National Council of

Textile Organizations, for example, each single textile job supports as many as three other U.S.

workers.

Other Costs

As important as labor costs are to maintaining mill health, they pale when compared to the

other big cost drain: fibers and other material purchases. Thus, last year — when material costs

skyrocketed — some 72 percent of the sales dollar for companies making basic mill products was

needed to cover these expenses. And the material cost bite for outfits making more highly

fabricated mill products like carpets and home furnishings was an almost-as-large 62 percent.

What happens here can make a tremendous difference as far as bottom-line performance is

concerned. And

TW

‘s projections here are basically upbeat. Looking first at cotton, which has been backing and

filling around the 70-cents-per-pound level for more than six months now, there’s little sign of

any real firming. Indeed, tags could well inch lower in face of current glutted market conditions.

A recent U.S. Department of Agriculture outlook study makes this oversupply crystal clear.

Put simply, it points out that with global production continuing to outpace global consumption,

world ending stocks of the fiber should rise substantially.

As for the specifics, global cotton use during the current crop year is put at 106.3 million

bales. That lags global production estimates, which are put at 116.8 million bales.

Result: Global stock levels by the end of the marketing year should jump to 80.3 million

bales. Zero in on the stocks-to-use ratio — a key cotton price barometer — and this year’s jump is

even more impressive — from 67.5 percent in 2012 to 75.5 percent for the current marketing year.

The other natural fiber, wool, also doesn’t seem to present any problems. Weak demand and a

lack of orders have pushed quotes down significantly since last spring.

More importantly, chances of any appreciable wool price run-up are practically nil — at

least not before late 2013 at the earliest. For one, a far-from-robust economy will limit any

demand gains. Then, too, wool growers have had to contend with the historical volatility of prices,

something that continues to convince some users — especially carpet makers — to switch over to

man-mades like polyester.

As for man-mades, prices here also have been a bit soft of late, largely reflecting recent

declines in petrochemical feedstock costs. As a result, man-made averages have slipped and are now

actually fractionally below where they were a year ago.

To be sure, there are also other costs to consider like transportation. True, they have been

rising, as have administrative expenses. But when all production and distribution costs are added

up, overall cost increases have been and should remain modest.

No Big Price Boosts

These relatively benign cost pressures should, in turn, help keep a lid on prices. Indeed,

there’s precious little to indicate anything more than a continuation of the extremely low textile

and apparel inflation rates of the past few decades.

Actually, the United States’ two industries have shown smaller increases than those recorded

in most other domestic manufacturing sectors for a long time. Overall, the long-term textile and

apparel average advance comes to less than 2 percent a year.

That’s pretty much an across-the-board pattern, too — with fibers, greige goods, finished

fabrics, industrial fabrics, home furnishings, and carpets all sharing in this slow creep-up. And

the same holds for apparel. In fact, the typical long-term annual advance in clothing tags has been

an exceptionally low 1 percent. Nor is all this likely to change any time soon. All signs point to

more of the same for this year, with the boosts likely to be even less than those posted in 2012.

One exception here could be for rugs and carpets. Here,

TW

doesn’t rule out somewhat larger price hikes — primarily because housing should be a lot more

robust than it has been. But even here, no really big increases are anticipated.

Costs, of course, aren’t the only reason for all this price restraint. There’s also excess

capacity — abroad as well as in the United States — an excess that’s likely to foster strong price

competition for what is essentially limited demand.

If there’s any doubt of the glut here in the United States, look back to the previously

noted low 70-percent operating rates that now seem almost sure to continue into the future.

The fact that the glut is across the board also suggests strong inter-subsector pressures.

What happens in one area, for example, can have an impact on another. Clearly, the harder it is for

clothing manufacturers to post hikes, the more likely they are to resist price boosting attempts on

the part of their mill suppliers.

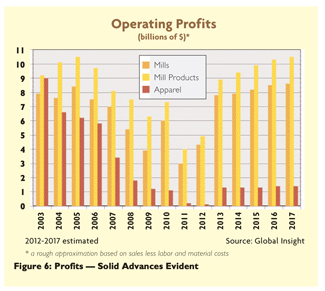

Profit Gains Ahead

But despite the lack of any meaningful price hikes, earnings and profit margins should

continue to post solid advances. Credit the gains to a combination of factors — the better cost

picture alluded to above, some modest uptick in demand, and stepped-up industry efforts both to

hold onto existing markets and to develop new ones.

In any event, this stronger profit picture is already becoming evident. Thus, Uncle Sam’s

latest — third-quarter 2012 — estimates show overall textile mill earnings for that three-month

period rising to $521 million, some 35 percent above the year-earlier numbers.

Apparel manufacturers also fared well. Here, the third-quarter 2012 after-tax take came to

$2.3 billion — a fair-sized 9-percent jump over the comparable year-earlier level.

A similar picture seems to be shaping up when it comes to both textile and apparel margins.

Specifically, third-quarter 2012 after-tax earnings per dollar of sales also have increased

vis-à-vis a year earlier — from 3.9 percent to 5.4 percent for mills; and from 8.8 percent to 9.8

percent in the apparel sector.

Look at another margin yardstick — after-tax earnings per dollar of shareholder equity — and

the numbers are even more impressive. For mills, the comparable year-to-year advance is from 9.8

percent to 12.8 percent. For apparel, it’s from 12.4 percent to 23.4 percent.

Unfortunately, government forecasts for the next few years are not available. But

TW

does have some estimates, courtesy of Global Insight, whose analysts, using their rough and

dirty estimate of profits — shipments less labor and material costs — see the 2012 earnings uptrend

continuing for years.

Dividing the mill sector into its two major subgroups, Global Insight projects a sold

earnings rise for both areas. For basic mill products, the earnings jump is from $4.3 billion last

year to more than $8 billion by 2015. As for the other subgroup — more highly fabricated products —

totals are expected to rise from $4.9 billion last year to just over $10 billion by 2015.

The most impressive gain, however, should be in apparel — primarily because recent earnings

have been depressed, as manufacturers were forced to work off all the expensive cotton they had

rushed to purchase during the fiber’s 2010 run-up. But that’s now about to change, with last year’s

near break-even level jumping to well above $1 billion profit levels over each of the next few

years.

Finally, a few words on all these rising dollar profit estimates. While clearly moving in

the right direction, there’s absolutely no way earnings will ever again approach the much larger

numbers of the past decades. The industry has shrunk much too much to permit any such bounceback.

As such, margins — relative rather than absolute earnings measures — should provide a much better

idea of the U.S. textile and apparel industries’ overall financial health.

More And Better Products

Meantime, U.S. companies have been increasingly active in their efforts to innovate and

improve. It’s a big part of a strategy to keep their firms not only viable but also profitable in

today’s hotly competitive global marketplace.

It’s an approach that potentially can pay handsome dividends. For one, there’s probably no

better way to whet consumer appetites.

Secondly, new, upgraded offerings generally command higher markups as well as increased

sales volume. A spokesman from market research company NPD Group, emphasizing the markup factor,

notes that much of the strength in dollar sales these days can be traced to consumers who, after

years of penny-pinching, are willing to splurge for something a little different or a little

better.

Not surprising, then, each year, the number of such premium products hitting the market

grows larger and larger. They cover virtually every segment of the market — including fibers, woven

and nonwoven fabrics, clothing, carpets, new industrial applications, and even garments embedded

with electronic components.

Putting the spotlight on fibers first, the innovations more often than not are being sparked

by new chemical breakthroughs, like recently developed new additives that help both degrade stains

and kill bacteria on cotton and other fibers when exposed to light. It could well point the way to

a market for self-cleaning clothes.

New antimicrobial technologies, meantime, can now also easily be integrated into nylon and

polyester polymers. The big selling point: lowering infection rates in such hospital items as

privacy curtains, linens, scrubs, and doctor coats.

And the list goes on and on, with still another chemical innovation aimed at blocking

ultraviolet light. The technique is already being applied to clothing and accessories like shoes

and umbrellas — with offerings available from such big outfits as Gap, Izod and Lands’ End.

Move over to apparel, and the picture is equally impressive. Washable and wrinkle-free

products are now more the rule than the exception. And the touting of these and other attributes is

no longer limited to one particular fiber or fabric. Makers of cotton, wool, man-mades and blends

now emphasize their products’ pluses in such areas as thermal regulation, moisture-wicking,

antimicrobial control, insulation, durability, water repellency, breathability, comfort and

biodegradability.

A few words are also in order on the increasing development and availability of so-called

advanced textiles. There’s now increasing potential for their use in aviation, automobiles,

military equipment and law enforcement.

Consumer goods aren’t being forgotten here either. One example is new apparel that

incorporates such extra features as conductive threads, sensors, batteries, and even small

microprocessors. Also coming are T-shirts that can shoot full-light videos or use GPS to point a

traveler to his/her destination.

Other Strategic Moves

While all of the above innovations have clearly played a major role in keeping U.S. textile

and apparel companies healthy, they are not the only factors behind recent successes. Given today’s

rapidly changing world and business climate, there’s a lot more that can be done — especially in

areas like sourcing, supply chain management, ecology, government help, development of niche

products, and improved quality.

Some of these subjects have already been touched upon. But some additional comments are

needed on a few of them. As for supply management, there’s the increasing need to keep inventories

and, hence, inventory carrying costs as low as possible.

The basic message from virtually every company’s CEO is the same: Keep stock levels low.

Worry less about long-term order problems and more about being lean, flexible, and in tune with

ever-shifting consumer wants and needs. In short, put more emphasis on stronger supply chain

networks — those that allow for low inventories and quicker reaction times to ever-changing market

demands.

A lot more attention is also being given to ecological demands. And with good reason: A

recent Cotton Incorporated survey finds more than two-thirds of U.S. consumers are now bothered if

they find that an item has not been produced in an environmentally friendly way. Most of these same

people also tend to blame the company making the product.

Not surprising, water conservation often gets the most attention, as a growing number of

technologies emerge that reduce both the amount of water needed and the discharge of wastewater

into the environment.

Also worth noting is industry group the Sustainable Apparel Coalition’s Higg Index, which

allows brands, factories and chemical manufacturers to score the relative sustainability of their

products. Eventually, the index aims to provide the data to consumers, perhaps on clothing hangtags

or websites.

An impressive number of large companies are already starting to use the index to measure the

effects of their fabric choices, pattern-making and waste products. Brands can get points for

asking consumers to wash items in cold rather than hot water — as Levi Strauss & Co. does — or

using recycled components like polyester made from used plastic bottles.

In another area, domestic firms are being helped by having Uncle Sam be more proactive in

protecting against unfair foreign competition. More steps are needed like the recent Washington

decision to participate in Chinese-Mexican talks on unfair Beijing subsidies.

Other moves involve the protection of intellectual property. This is something that can

likely help the U.S. industry, as 5 percent of all complaints here have been in the clothing field.

Free trade pacts can also contribute to industry well-being. At the moment, there are

negotiations to establish a Trans-Pacific Partnership involving Pacific Rim countries. This is in

addition to the 46 already existing free trade agreements.

Still more trade help could be coming from the U.S. National Export Initiative program

started a few years back. It could be one reason why U.S. outgoing shipments of textiles and

apparel have sported double-digit gains over pre-initiative levels.

Another approach that’s paying off is the development of more niche products. Big domestic

outfits like Milliken & Company, for example, have gradually been diversifying out of

traditional textiles and into specialized markets. Result: These companies’ revenues and profits

have been climbing.

In another marketing tactic, there’s the stepped-up emphasis on quality. It’s clearly

something that consumers want, if a recent Cotton Incorporated survey is any indication. Note that

respondents rated “higher quality” twice as important as “more fashionable” when choosing a new

garment.

Domestic producers are also bolstering demand by stressing that their products are made here

in the United States. Again, a relatively recent survey, one indicating that nearly 90 percent of

buyers prefer to support the U.S. economy, would certainly seem to justify this approach.

To sum up: If there’s anything that best characterizes all the above strategies, they’re the

words “flexibility” and “change.” The good old days of just maintaining the status quo are gone.

The big winners from here on will be those companies willing to move quickly and decisively when

new or innovative opportunities present themselves.

And indeed, judging from all the evidence, that’s becoming more and more the mind-set of the

U.S. industry. In fact, that’s one of the key reasons why

TW

is so confident that the firming demand and rising profit trends of the past few years will

continue through the foreseeable future.

January/February 2013