F

ashion trends are production challenges faced every day by a textile finisher. The goal

is to produce first-quality goods only. This is especially difficult when weft distortion has been

introduced to the fabric during various process stages.

Uneven tension distribution across the weft is the main cause for distortion. There are many

causes for this defect, including tension variations, equipment lineup, improper roller adjustments

and direct contact of machinery with the material.

Dealing With Weft Distortion

Mechanical forces are commonly employed to correct the geometry of a weft that has been

distorted during the finishing phase. Both mechanical weft straighteners and differential drive

tenters are commonly applied technologies.

By adjusting the speeds of differential tenter chains, or by applying linear tension and

passing material across rollers that can be pivoted around the center point of the fabric width,

the weft lines can be moved and realigned.

Mechanical weft correction devices have always been used to correct weft distortion,

primarily on materials where distortion is more visible and becomes an issue for the end-user.

However, as tolerances grow tighter, production speeds increase, and the fabrics become more

complex, automatic weft straightening is a must in today’s modern textile finishing operations.

Using photoelectronic detection in oscillation removes possible mechanical difficulties.

Straightening Principles

The history of automatic weft straightening goes back more than 40 years. Generally, there

are two common automatic weft-straightening principles used today: automatic straightening by means

of mechanics; and automatic straightening by means of electromechanics.

Automatic straightening by means of mechanical force is based on the parallelogram effect.

When the distortion of the fabric is along a diagonal axis, the warp and weft geometry, initially

orthogonal, assumes a parallelogram configuration. When the two selvages are pulled out to stretch

the cloth to its full width, the weft is tightened, generating complex forces in a parallelogram

configuration to establish a square structure. This straightening force can be exploited for

restoring proper weave geometry if the selvages, in spite of their lateral tensions, are

sufficiently free to move in the direction of the warp.

Automatic straightening by means of electromechanics is the most common method employed

today. Weft geometry is automatically detected using a mechanical or electrical sensor. That

information is then transformed into a signal that displaces rollers, making the correction as

necessary. The weft-straightening effect here is the result of the difference in distance traveled

by one selvage in relation to the other over the rollers in the weft-straightening system.

Sensing Technology

In order to have an effective automatic weft-straightening system, it is important for the

sensing device to detect all the possible fabric styles, designs, colors and structures. With

today’s complex textile products, that is not always an easy task. The ideal detection system is

capable of sensing denim, sheeting, jacquard, apparel and automotive fabrics; fiberglass, carpet,

lace, terry towels and a large variety of technical textiles, among other products.

In the early 1960s, two major detection systems on the market were used for detecting weft

distortion in fabric. One system involved the use of mechanical principles, and the other utilized

photoelectronic sensors.

Mechanical Detection Principle

The mechanical principle is based on the use of two wheels mounted on a freely moving

mounting pin. Under normal conditions, both wheels are turned by the passing fabric, resulting in a

homogenous signal. When a distortion is sensed, the tension created by the skewed weft causes the

freely mounted wheels to turn left or right depending on the distortion. A non-proportional signal

is generated by a differential amplifier, sending correction signals to a correction device. As

long as the wheels in continuous contact with the material remain in the same good working

condition, the measurement results remain satisfactory. Any uneven fabric surface challenges the

mechanical principle and generates asymmetrical distortion. This system has not been further

developed in its design and has been discontinued because of limited detection abilities and

hardware reliability.

Photoelectronic Detection Principle

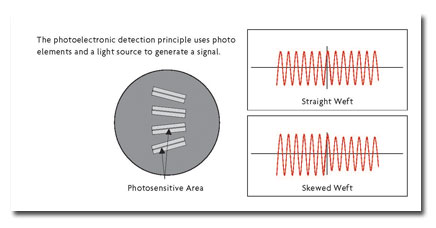

The photoelectronic sensor is based on a signal modulation created by the passing web

structure. One of the first photoelectronic sensors was based on several photo elements located on

one side of the web and a light source on the opposite side of the web. When the weft line was

parallel and straight in front of the sensor, a somewhat equally strong signal was generated in

both channels.

If the weft line was not parallel to the sensor, one pair of photo elements generated more

signal than the other, and this determined the distortion. That type of sensor could only

differentiate between left or right distortion and was not able to quantify the amount or angle of

distortion. Therefore, a proportional correction based on the physical distortion was not possible.

The next generations of optical sensors utilized only one photo element by letting it freely

oscillate between known limits. That improved the linearity, resolution and accuracy of each

sensor, enabling it to detect more complex fabric structures.

With microcomputers entering the industrial arena, it was not long until the first

microcontroller-based detection system was introduced. Stepper motor technology for linear movement

replaced the free-oscillation detection lens and improved lighting principles such as infrared

light-emitting diodes and reflex light sources, bringing the system more up-to-date.

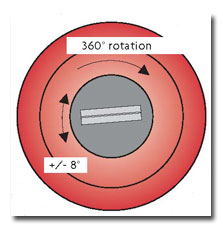

The photoelectronic detection technology is utilized in various executions such as

oscillation, rotation or shifted dual-rotating mode. By rotating the lens 360º instead of always

oscillating on the same position, one could avoid possible mechanical difficulties. However, there

is some valuable time lost by scanning areas of the fabric that are unrelated to the weft line. The

shifted dual-rotating mode reduces such time delays in collecting valuable weft distortion

information with a two-lens system.

The latest CCD matrix camera from Erhardt + Leimer GmbH employs high-resolution auto-focus

and auto-zoom technologies.

Weft Detection Using Cameras

The rapid reductions in the prices of computer systems and digital cameras combined with

advanced image-processing techniques have led to the introduction of several vision systems to the

textile manufacturer. There are two types of camera systems that can be used to create an image:

line scan camera technology; or charged-couple device (CCD) matrix camera technology.

The line scan camera in combination with an encoder creates an image while the web passes

by. After capturing the image, the evaluation software uses special algorithms to process the

digital information.

The line scan camera technology typically is used to detect the full width of the web,

detecting and evaluating patterns rather than the weft line. That can be realized with either one

or two cameras, depending on the area of interest. However, if there is no pattern in the web, the

line scan technology is not able to detect any distortion in a web.

A matrix camera takes images similar to any conventional digital camera on the market. The

web is imaged several times per second, whether running or not, on a 2-D area. The camera looks at

multiple weft lines simultaneously, providing a high data rate of the passing weft structure. With

sophisticated software tools and mathematic calculation, a 3-D image is processed, detecting not

only the weft, but also the warp of a web.

The matrix camera technology is used for a closer look at the individual weft and utilizes

the weft structure in its calculation of the residual web distortion. Whether with several cameras

evenly distributed over the full width of the web, or just one scanning camera taking images

across, a large cross-direction and machine-direction profile of the passing web is captured. A

reflecting circumference infrared illumination guarantees the best uniform imaging results.

The latest camera introduced from Germany-based Erhardt + Leimer GmbH employs

high-resolution auto-focus and auto-zoom technologies that allow the camera to view an optimum

evaluation area and the largest 2-D area possible. The camera is mounted 250 millimeters away from

the web, moving it away from sometimes harsh existing environmental conditions. The image is then

processed within a 3-D space and filtered through a fast Fourier transformation (FFT), resulting in

spectral data. Separating the noise from the actual high-level spectral data leaves the positioning

information of the weft and the warp.

A major breakthrough of the 2-D image detection system using CCD matrix camera technology

makes detection on many difficult webs such as carpet, jacquard and thicker wefts a problem of the

past. Whereas conventional photoelectronic systems detect one weft at a time, the CCD matrix camera

has the ability to evaluate a large number of weft lines simultaneously, even if the web is not

moving. And whereas conventional photoelectronic sensors are required to have a minimum speed for

detection, the speed of the process has no influence on the final result or the quality of the

evaluated detection area when using the CCD matrix camera.

In addition to increasing the number of weft lines being detected, the system with its wide

field of view also has increased drastically the evaluation area in the cross direction of the

weft. That makes it more accurate and reliable because it sees far more than conventional detection

systems see.

Many disadvantages associated with conventional detection systems can be overcome by using

image-processing techniques to monitor webs of all kinds. New camera measurement systems have

improved the range of use from unstructured, homogenous webs to complex, patterned fabrics.

Higher-quality products and more satisfied customers result from more accurate and reliable

technologies.

Editor’s Note: Udo Skarke is manager of Germany-based Erhardt + Leimer GmbH’s Textile Division

in Duncan, S.C.