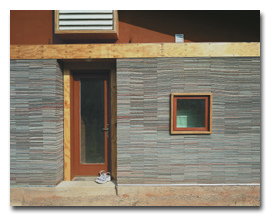

Interface supplied carpet tiles made from recycled materials for interior and exterior

walls of the Lucy House – part of the Rural Studio Project Photography courtesy of Timothy

Hursley.

W

e all like the feel of soft carpet under our feet. It is a feeling of comfort, warmth and

luxury. But next time you rip up your old rugs to lay down new carpet, spare a thought for the fate

of your old floor covering.

Most used carpet ends up in a landfill. While it represents less than 3 percent of the overall

volume of waste landfilled each year, more than 4.5 billion pounds of carpet were discarded in the

United States in 2004, according to estimates from the Dalton, Ga.-based Carpet and Rug Institute

(CRI).

Given the growing scarcity of landfill space and the acceptance that recycling and sustainable

manufacturing processes can actually make business as well as environmental sense, a large number

of carpet manufacturers signed a Memorandum of Understanding for Carpet Stewardship (MOU) in 2002.

Its main goal is lofty a landfill diversion rate of 40 percent by 2012. This target is viewed as a

step towards a long-term commitment by the carpet industry for the eventual elimination of not only

disposal in a landfill, but also incineration and incineration with energy recovery

(waste-to-energy) of waste carpet.

So how is the effort shaping up? It certainly got off to a bad start when, in 2002, Evergreen

Nylon Recycling LLC – a joint venture between DSM Chemicals North America Inc., Augusta, Ga., and

Honeywell International Inc., Morris Township, N.J. – closed its carpet recycling facility in

Augusta. This closure was followed by the bankruptcy of the Germany-based Polyamid 2000 plant in

2003.

These plants used the latest technologies to recycle the nylon content of old carpets. Evergreen

used selective pyrolysis to produce caprolactam from nylon 6 carpet fibers. Caprolactam is the main

chemical building block of nylon 6, so Evergreen’s process offered closed-loop recycling for nylon

6 carpets. Polyamid 2000 was able to recycle nylon 6,6 carpets using a proprietary process. Energy

was recovered from the non-recyclable, organic portion and used to power the plant.

But the economics just didn’t add up, as several European research projects could have

predicted. According to Edmund Vankann, managing director of GUT – a Germany-based consortium of

European carpet manufacturers focused on promoting environmentally friendly practices – polyamide 6

is the only polymer that can be recycled into a product of real economic value. Theoretical

research shows only about 4.5 percent of an incoming carpet waste stream in Europe is polyamide 6

– about half the amount necessary to make the process worthwhile financially. Unsurprisingly,

by 2004, nylon carpet recycling was almost non-existent.

Nevertheless, Bob Peoples, director of sustainability, CRI; and executive director, Carpet

America Recovery Effort (CARE), an affiliate of CRI, remains upbeat. “This is not a dying but

nascent industry, but the timing in the economic cycle is not right. Still, what has become clear

to me over the past few years is that the free enterprise approach is the right way to solve this

challenging problem and that, ultimately, society must bear the cost of sustainability.”

Recycling Initiatives

Carpet manufacturers are leading the way with recycling initiatives. INVISTA Inc., Wilmington,

Del., operates the oldest planned carpet recycling program, accepting carpet regardless of fiber

type, manufacturer or backing type. Post-consumer carpet products recycled include carpet cushion,

automotive parts, natural turf-based roofing tiles, furniture, pallets, filtration pipes and

boards.

Some companies such as Interface Inc., Atlanta; and Milliken Carpet, LaGrange, Ga. have reuse

programs. They take back old carpet tiles, and clean and refurbish them, even adding new color and

patterns. But reuse accounts for only a tiny portion of carpet diverted from landfills. “While

reuse provides an interesting story, reuse will never offer significant diversion of carpet from

disposal,” said Dobbin Callahan, general manager, government markets, Tandus US Inc., parent

company of a number of floor covering businesses, including Dalton, Ga.-based Collins & Aikman

Floorcoverings Inc. (C & A). “I think it is fair to say that reuse by all companies

involved does not account for one-tenth as much recycling as we alone are doing!”

Recycling of material is much more important, and most carpet manufacturers now include recycled

content in their carpet ranges, especially in the backing polymers. C & A takes polyvinyl

chloride (PVC)-backed carpet and recycles it into backing for new carpet.

Shaw Industry’s A Walk In The Garden Collection of carpet tile, which contains Ecoworx®

polyethylene carpet backing, is designed for convenient recycling.

“We take the old material, chop and grind it, pulverize it and pelletize it and then extrude it

to produce new, 100-percent recycled-content backings,” Callahan said. “We are recycling 10 million

pounds of carpet per year this way. PVC recycling is economically viable for sure. Today, it is

cheaper for us to make a tile with recycled PVC than to use virgin material.”

Manufacturers also are beginning to consider recycling in the design of their carpets. Dalton,

Ga.-based Shaw Industry Inc.’s EcoWorx® polyethylene backing – just one end product created from

its many recycling and sustainability efforts – is designed specifically for easy recycling. The

company also has a cradle-to-cradle design protocol to assess each individual material used in a

product to determine whether it is safe for the ecosystem.

Callahan believes the market for carpet recycling will grow substantially. The change will come

about when the main purchasers of carpet begin to demand recycling and products with recycled

content. It is not a major issue for the education or health care sectors yet, but in government

and in corporations, sustainability is beginning to get higher up on the agenda. Corporations need

to maintain an image of environmental concern, and government needs to lead the way in diverting

waste from landfills. Most of the market is driven by how new carpets are specified – there are no

mandates yet, but plenty of initiative to encourage recycled content.

Peoples looks to entrepreneurs to take up the carpet recycling challenge. “CARE is keen to work

with the little guys,” he said. “There’s no way we have the technology today to put 2 billion

pounds of post-consumer carpet back into carpet,” Peoples said. “We have to find other outlets. It

is like a great mosaic, putting in many pieces to achieve the overall goal. Creation of demand for

such products will be a critical key to the success of CARE.

TieTek has developed railroad ties that incorporate a mixture of carpet materials,

plastics, rubber from recycled tires, other waste materials, chemical additives and various fillers

and reinforcement agents.

Peoples highlighted several innovative materials and products he thinks epitomize the direction

carpet recycling should take. Atlanta-based Nycore Inc., for example, has seen considerable growth

in its business. Post-consumer carpet is sorted, separated and mixed with other components before

being extruded into a board. It is an ideal substitute for wood and plastic building materials. The

company’s products include Nycore, a 100-percent post-consumer-carpet thermoplastic tile

backerboard; and Ny-Slate, a 100-percent post-consumer-carpet roofing tile.

TieTek LLC, Houston, is developing railroad ties that incorporate carpet materials. The novel

composite tie is composed of a proprietary mixture of plastics, rubber from recycled tires, waste

materials, chemical additives and various fillers and reinforcement agents. In extensive field

tests, they have proven to be superior to wooden crossties, lasting up to 50 years, according to

the company. They also are fully recyclable at the end of their useful life. Fifteen million

railroad ties are used each year, and they require creosote a human carcinogen as a preservative.

“These composite ties tell a hugely compelling environmental story,” Peoples said.

Old carpet also may find its way into plastic lumber or specialty products such as drain

sediment filters, which outlast natural hay.

Making It Work

GUTs Vankann is skeptical about whether this entrepreneurial model would work in Europe. He

noted that the main products developed so far are probably not appropriate in Europe, where timber

is rarely used in construction and railroad ties are made of concrete.

“In Europe, we have taken a technical approach,” he said. “We wanted to know the basic facts

first, whereas in America they are concentrating on making products and creating new markets. Our

research suggests the problem of separating and collecting has to be overcome first if we are to

recycle large quantities of carpet. Niche products are only part of the solution.”

For Europe, which has no carpet reclamation infrastructure, Vankann said recycling efforts will

have to start off looking at energy from waste. Research suggests carpet is a better fuel than

brown coal. Carpet is highly efficient and perfect for refuse-derived fuel, he explained. It should

be collected up with other high-calorific waste sources to produce refuse-derived fuel (RDF) waste

to energy. Once the RDF infrastructure is in place, it may then be possible to look at separating

materials from this waste stream for chemical or other recycling. The RDF solution is best for

those products made 10 years ago, when nobody thought about designing carpets for easy

recycling.

Peoples is keen to explore every possible opportunity available in order to reach the recycling

targets. “There needs to be a variety of outlets and uses,” he said. There is also a role for

cement kilns and energy recovery in our overall plan, but by creating many product outlets for old

carpet as a raw material, it will be easier to accomplish our aggressive goals. The key to success

will be creating demand for products that contain post-consumer recycled content from carpet. I

believe a good portion of our challenge is to get the word out, communicate and share the story of

the new industry we are creating a new industry based on sustainable design.”

April 2005