A

standard technique for measuring marketplace maturity is Product Life Cycle Analysis. All

product or service classes progress through four predictable life stages from birth to death –

introduction, growth, maturity and decline. In the introductory phase, products demonstrate great

variety and heavy infusions of innovative thinking. The market is small, and there are few

competitors.

In the growth phase, product success is assured, and prices are declining so as to be

attractive to a wider slice of the population. Despite declining prices, competitors appear to

challenge the leader, because there is now sufficient demand and margin for a few more entrants.

Brand identification becomes important.

In the maturity phase, growth slows or stops; prices drop precipitously; competitors

disappear through failure, merger or absorption under the guise of larger is better; brands drop

away; and innovation evaporates. Industry profits, which peaked early in the growth phase, drop to

zero or negative, and are recognized by frenetic cost cutting in an effort to survive.

Lastly, in the decline phase, few producers remain, prices stabilize and sometimes rise, as

suppliers race to redirect invested capital in new products and markets with greater opportunity

for returns. Additionally, those products that remain become less standardized, as the market

approaches “niche” status, with customers willing to pay premium prices to obtain the now

“obsolete” products.

Sound familiar? Where do fibers and textiles fit in this continuum between introduction and

decline?

While some colleagues in the contemporary textile industry press are ready to write off the

entire industry as incapable of creating satisfactory profits, a careful reading of the business

press seems to indicate otherwise. Some producers are thriving, some are reinvesting, and a few are

emerging from bankruptcy much stronger than when they entered the court’s protection. Admittedly,

while many investors lost significant dollars in the past five to eight years as the industry

swooned, a few hardy folks are reappearing as active investors in what remains of the US textile

industry. Do these people know something others do not? Is there a pattern in their investments

that can lead us to a new definition of the domestic textile market? As Alasdair Carmichael of

United Kingdom-based PCI Fibers & Raw Materials asked rhetorically at the summer 2002 meeting

of the Textured Yarn Association of America (TYAA), “If this were a sunset industry, … would

there be overseas investment? It is clear that some heads think that textiles in the United States

still is an industry worth [investment].”

Methodology

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis and

Retrieval System (EDGAR) website is a jewel for data-mining information about operations, finances

and ownership of public companies.

Several fiber and textile companies were examined to uncover a pattern of outside investment

in the industry.

Textile World

‘s interest comes from trying to balance the historical dominance of private ownership in

textiles against the current need for capital investment to remain world-competitive in the face of

the well-documented import flood. Textile companies, whose futures have been affected by the

investment-numbing problems of stocks with low or no value, and poor markets with low or no

profits, have pushed the industry to the back of the investment capital waiting line. At a time

when directing new investments to new technologies is imperative in global competition, the stars

have aligned to exclude textiles from the party.

Despite this logic, some investors actively are placing significant funds in fiber and

textile companies.

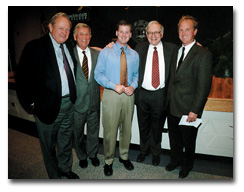

In 2001, Berkshire Hathaway acquired Shaw Industries. From left to right: Former Chairman

J.C. “Bud” Shaw, Chairman and CEO Robert E. “Bob” Shaw, Sales Representative Jason Shaw, Warren E.

Buffet, and Executive Vice President Julius C. Shaw.

Man-Made Fiber Producers

At the risk of generalizing, it is almost fair to say that substantial investment in the US

man-made fiber industry comes from international sources. Except for Kingsport, Tenn.-based Eastman

Chemical Co.’s acetate, an appendage to the huge volume of cigarette tow, cellulose

production is totally controlled by international firms. Polyester remains US-dominated by DuPont,

KoSa and Wellman, but even these companies are spreading their wings toward outside investment.

In 1998, DuPont, Wilmington, Del., spun off its staple fiber business into DAK Americas,

Charlotte, a joint venture with Mexican petrochemical manufacturer Alfa S.A. de C.V. While

appearing to strengthen DuPont polyester with new investment, the move may in turn have

strengthened other non-fiber DuPont products by passing fiber debt onto DAK.

Two years later, DuPont and Unifi Inc., Greensboro, N.C., announced an alliance to mutually

plan and produce polyester filament yarn. The goals were similar to the DAK transaction (reduce

cost), although the methodology was different. The objective of the alliance was to “reduce

operating costs through collectively planning and operating both companies’ manufacturing

facilities.” Each participant retained ownership of its facilities, but the alliance planned and

operated the facilities in concert. Each participant, through a series of put options, could

purchase the alliance from the other partner. Needless to say, neither DuPont nor Unifi has

exercised the options.

KoSa, Houston, originally was a joint venture of Koch Industries, Wichita, Kan., and IMASAB

S.A. de C.V., a company controlled by Mexican billionaire Isaac Saba, to buy the Hoechst Trevira

polyester operations. The venture was derailed in 2001, when Saba backed out and sold his share to

Koch. KoSa since has taken its total ownership role to heart and remains committed to being “the

‘state-of-the art, lowest-cost producer’ in the markets it serves.”

Wellman Inc., Shrewsbury, N.J., producer of Fortrel® polyester and one of the world’s

largest recyclers of post-consumer polyester materials, has maintained a fierce independence

throughout its history. Committed to expanding its Pearl River, Miss., facility, the company sold

its Fayetteville, N.C., polyester filament plant to Cedar Creek Fibers LLC; converted staple

production in Palmetto, S.C., to bottle resin; converted planned staple fiber production in Pearl

River to bottle resin; agreed to provide amorphous polyester chip to Eastman Chemical for bottle

resins; and accepted a $125 million preferred stock investment from Warburg Pincus LLC, a global

private equity firm. The timing suggests that Warburg is financing the conversions to bottle

resins.

By way of introduction to nylon, the apparent desire of DuPont to spin off its entire fiber

group must not be ignored. In addition to the polyester alliances, DuPont has nylon 6,6 as its

largest poundage volume product and Lycra® (spandex and non-spandex comfort items) as its signature

marketing approach. Carpet fibers, which represent a significant portion of DuPont nylon products,

have done well and are forecast to continue to do so. Nonetheless, nylon is not a new technology

material and is viewed by the investment market as a drag on DuPont’s avowed metamorphosis into a

high-technology company. Market rumors abound about DuPont’s disposition of the remaining fiber

positions. Because nothing is firm, further comment is not necessary.

Last, but not least, in January, Honeywell, Morris Township, N.J., and BASF Corp., Mount

Olive, N.J., announced a business swap whereby Honeywell will acquire most of BASF’s nylon fiber

business plus cash, and BASF will acquire most of Honeywell’s engineering plastics business. Each

of the two businesses’ revenue streams approximate $350 million, which, when added to their new

owners’ portfolios, brings the resulting businesses to the critical mass needed to compete

globally. Honeywell will trade a relatively small plastics business for a nylon carpet, industrial

and apparel fibers business, which will drive its nylon commitment to more than $1 billion in sales

per year. Unstated in the public announcements, but a logical component of the swap, will be

increased usage of Honeywell’s nylon caprolactam capacity. Additionally, BASF will continue its

retrenchment from consumer products to the upstream industrial markets featured in its advertising

slogan: “We don’t make a lot of the products you buy. We make a lot of the products you buy

better.™”

Textile Machinery Producers

Consolidations of textile machinery companies make sense in cases where they eliminate

excessive costs, allow customers to easily view and select from many alternatives, and encourage

elimination of the competitive duplication that accompanied the individual companies.

Two mergers come to mind. The St. Louis-based Harbour Group has assembled, under the

Tube-Tex banner, a family of formerly independent suppliers of finishing equipment for knitted

fabrics. Included in the assembly are: Tube-Tex with compaction/drying and padding machines;

Marshall & Williams with tenter frames; JEMCO with continuous bleaching; RFG with raising and

napping equipment; and Ashby, selling fabric-handling equipment for dyehouses. The advantages of

selling multiple lines include extending venerable brand names and establishing the groundwork for

a global business model.

Similarly, Italy-based Itema Group, a subsidiary of the RadiciGroup, Italy, has assembled a

group of companies that manufacture and sell a complete range of weaving machines appealing to a

broad choice of woven fabric constructions. These include Somet and Vamatex rapier and air-jet

looms; Sultex rapier and projectile looms; and the alliance with Toyota Industries Corp.’s

(formerly Toyoda Automatic Loom Works Ltd.) air-jet technology.

Textile Manufacturers

Until just recently, the most obvious place to examine textile investments involved the

previously announced bid to purchase Greensboro-based Burlington Industries Inc. by Berkshire

Hathaway Inc. Omaha, Neb.-based Berkshire announced it was terminating its offer after losing a

question in bankruptcy court about the court-mandated Burlington auction/sale of assets.

(See ”

Textile

World News,” March 2003). Berkshire’s interest in textiles is not new. Its legacy in

textiles includes Shaw Industries Inc., Fruit of the Loom and Garan Inc.

Two interesting counterpoints to the Burlington scenario involve the latest actions of

Heartland Industrial Partners L.P., Bloomfield Hills, Mich., with moves at Springs Industries Inc.,

Fort Mill, S.C., and Collins & Aikman Corp. (C&A), Troy, Mich. Historically a textile

company, C&A has moved deliberately toward redefining its mission while still maintaining a

foot in the textile marketplace. Several years ago, the Blackstone Group, a New York City-based

private equity investment company, invested in C&A and started transforming it from a textiles

supplier to a “global leader in the design, engineering and manufacturing of automotive interior

components.” C&A divested its apparel fabric operations and, in 2001, added the automotive

fabric operations of Joan Fabrics to its manufacturing base. Joan and C&A long have had major

relationships with the automotive industry as body cloth suppliers, and these connections formed

the basis of company moves to become a broader supplier of automotive products.

Also in 2001, C&A rounded out its product line by adding two other divisions. It

purchased Becker Plastics LLC, a major supplier of plastic components to the automotive industry,

and TAC-Trim, Textron Inc.’s Automotive Trim Division.

These purchases were financed with additional investment. David A. Stockman, director of the

Office of Management and Budget during the Reagan administration, was a senior managing director of

the Blackstone Group when the original C&A investment was made. In 1999, Stockman was a

founding member of Heartland Industrial Partners, with a mission to “purchase and invest in select

industrial companies … [in] the midwest area of the country.”

In 2001, Heartland, to help pay down debt and finance TAC-Trim, purchased a controlling

interest in C&A and acquired the right to a controlling interest on the Board of Directors.

Stockman’s investment participations at Blackstone featured leadership roles in several “old

economy” firms. It does not appear Heartland will do differently.

Similarly, Heartland participated in taking Springs private and refinancing its debt. Before

the private transaction, the Close family (and trusts) owned or controlled approximately 41 percent

of Springs’ common shares, which represented approximately 73 percent of the voting power of the

same stock. Heartland added approximately $225 million of its own equity to around $1 billion from

J.P. Morgan Chase to raise the Close interests to approximately 55 percent and provide Heartland

with a 45-percent position. Most important, the Close family was able to monetarize its stock

position and still retain control of the company, and was also able to provide valuable capital to

allow the company to restructure and reorganize to face the 21st-century market.

It appears that outside investments in textiles display constancy in two areas. First, the

investment community apparently has not soured on textiles per se. It stands to reason that fiber

and fabric manufacturing for apparel in the United States are under pressure from foreign suppliers

and cause concern for investors. Conversely, the same investment community is displaying interest

in textiles focused on home fashions and industrial end-uses. Smaller lots (including prints)

appear to insulate home fashions from imports. The logistics of shipping carpet likely will

continue to close off this product line from imports. And there is a need for specification-driven

product development alliances. All of these factors will help keep high-value-added textile

products “Made in America.”

Editor’s Note: Most of the data cited in this article comes from an accumulation of individual

reports filed with the SEC.